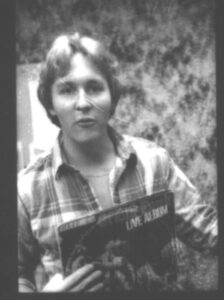

As my roommate at Ohio University 43 years ago, Doug Hill was vibrant, witty and intelligent. He was a radio DJ, a joke writer and stand-up comedian. After college, he became a successful advertising copywriter in Chicago and studied comedy with the famed Second City troupe.

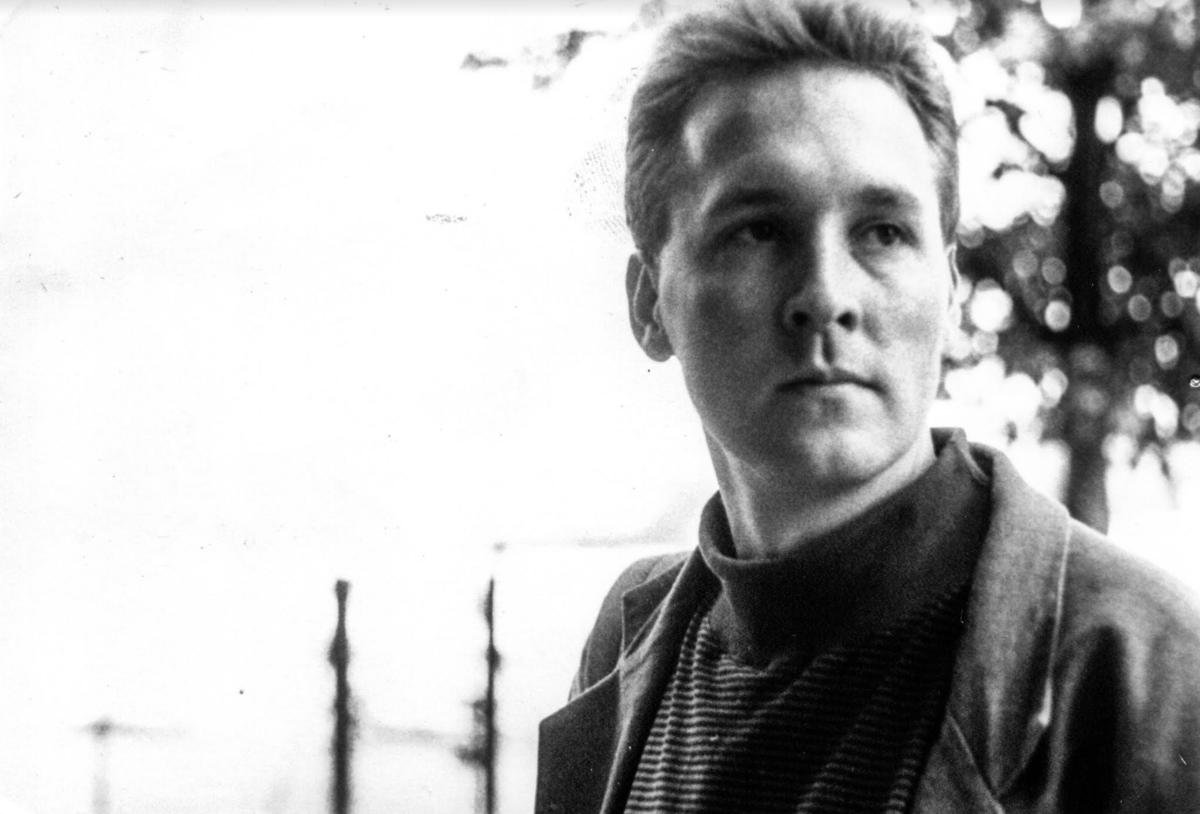

Handsome as ever, he showed little physical evidence of his illness as it began to take hold.

Yet, at age 38, he could no longer tell a joke. He rarely smiled. He couldn’t drive. He struggled to count change at a grocery checkout counter, frustrating clerks. He often sat silently, unable to carry on a conversation.

So when news came this week that actor Bruce Willis has been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, it instantly reminded the friends of Doug Hill that we had seen this movie before. It is a horror film.

The thought of Willis and his family going through what Doug and his family endured for years with this rare degenerative brain disease is to relive a nightmare.

Doug died in 2005 at age 45. His widow, Julie, and their son lost Doug in his prime. Doug learned in 1999 that he had the illness, which is also called frontal lobe dementia. It attacks the brain much the same as Alzheimer’s disease, but it favors younger victims, claiming people under age 65, often in their 30s and 40s, neurologists say.

The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration says an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with the illness, but that experts believe the number of people living with the disease is likely higher because doctors don’t always recognize symptoms as dementia.

An Australian researcher estimated at the time of Doug’s diagnosis that frontal lobe dementia occurs one-tenth as often as Alzheimer’s. With Alzheimer’s afflicting some 4 million U.S. residents at that time, it would have meant that about 400,000 people were suffering with frontal lobe dementia.

High-profile Alzheimer’s cases – such as that of former President Ronald Reagan – prompted Congress to spend more money for research. The National Institutes of Health estimates that $3.3 billion will be spent on Alzheimer’s research this year. That’s a good thing.

But far less is known about frontal lobe dementia, and NIH estimates that $164 million will be spent this year on its research. “Currently, researchers are at work on at least six clinical trials for disease-modifying drugs; that number will grow as greater attention is paid to FTD and its devastating impact on families,” the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration says.

Even if Congress had moved at lightning speed in the late 1990s to provide more research funding when Doug’s brain was shrinking, it wouldn’t have saved him. But additional research could help others who could have inherited genes related to the illness.

The disease is more likely to strike members of families with a history of it. That the next generation could suffer the same fate is a crime. They could be unsuspecting carriers of an illness that eats away the victim’s brain.

Here’s how I described Doug’s decline in a column I wrote for The Dispatch in 2001:

My friend shaved his eyebrows.

On another day, Doug sifted through mail – mostly junk – a dozen times in a matter of hours, each time as if it were the first.

Obsessed with removing a spot of paint from his jeans, he washed and dried them six times within a few hours, using a gallon of detergent.

Unable to start the coffeemaker one morning, he took a knife and cut out several offending pieces. The machine, filled with fresh grounds and water the night before, required only the flip of a switch.

He spoke in two- or three- word sentences and, like a tape recorder stuck in a loop, repeated them.

“Miles Davis. He’s dead. He’s over.”

“Miles Davis. He’s dead. He’s over.”

He fixated on death, perhaps because it was so close.

Julie heroically held together her family, balancing a career with the contrasting needs of an engaging child and a man she no longer recognized as the person she had married. She received support from family, friends, co-workers and a church but still carried a burden that would have crushed many others.

She shared their story in an episode of This American Life called “One Brain Shrinks, Another Brain Grows” that gives raw insights into what their lives were like at that time.

In the year 2000, Doug participated in an NIH study. We learned that his IQ had dropped 50 points, his brain was continuing to atrophy and show signs of scar tissue, and he was losing his ability to swallow. The disease eventually robbed him of many basic physical abilities.

He died in a nursing home surrounded by people twice his age.

Another thing we learned at NIH was that more money would be spent on Doug’s care than was dedicated nationally at that time to finding a cure for the disease. The cost of care for families and society is substantial.

Researchers noted in a study published in the journal Neurology in 2017 that “although the absolute number of patients with frontotemporal degeneration is lower than the number with Alzheimer’s Disease, the economic burden of frontotemporal degeneration is substantial. One of the key factors to this burden may be the earlier age at onset, typically occurring during patients’ or caregivers’ peak earning years.”

While some progress has been made toward understanding the cause of frontotemporal dementia, there is still much to learn and there is no cure.

It remains discomforting that the call for research money is but a whisper amid the many cries Congress and other potential funders hear. But if not for such whispers, AIDS and Alzheimer’s research might not have received the support needed to save lives from those diseases.

With no celebrity sufferer until now to help raise awareness of frontal lobe dementia, Doug’s family and friends have been his champions.

We established a scholarship in his name for Ohio University students who, like the two of us, were pretty average students who showed potential for greater things.

We also asked Congress to provide more funding for the study of frontal lobe dementia.

And now, we pray for Bruce Willis and his family – and that with a celebrity sufferer, many others will join the chorus by writing to their representatives for the sake of thousands of others who might one day face a similar fate.

Alan Miller is a former Dispatch editor who writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism Program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation.