A poisonous weed taking hold in fields, roadway ditches, fence lines and yards, is easily mistaken for wild carrot tops.And while the weed is from the carrot family, it can be dangerous for humans and even deadly for mammals, especially farm animals and pets if they ingest it.

The wispy, brilliant-green leaves of the poison hemlock plant can look like benign bright fern-like plants amid the still-brown weeds in early spring. But if not managed now, those little plants soon will shoot up into giant stalks 6 to 10 feet tall.

Experts say it’s one of the deadliest plants in North America.

“Poison hemlock plants contain highly toxic piperidine alkaloid compounds, including coniine and gamma-coniceine, which cause respiratory failure and death in mammals,” writes Joe Boggs, of the Ohio State University Extension Service, on the organization’s website. “It is the plant the Greeks used to kill Socrates, as well as the Greek statesmen Theramenes and Phocion. Indeed, the genus name Conium is Greek, meaning to spin or whirl, and refers to the symptoms of poison hemlock poisoning.”

Jim Bidigare, a Licking County real estate agent, said he has seen the plants in many places, including a patch of them along a set of stairs on the Denison University campus. The plants emerged near a bench on a wooded hillside about halfway up the stairs.

“Nobody talks about it,” said Bidigare, but added that conversation is urgent because the plant is showing up in many more places than in the past decade. “It’s been around for five or six years.”

The poison hemlock’s invasive nature and its potential to sicken or kill mammals “should be a concern of not only citizens that run into it, but especially to farmers,” Bidigare said.

Because it is growing along fence lines and near farm fields, one concern is that it could accidentally end up in grazing pastures or in animal feed, such as hay.

The plant can be seen growing in many places in Licking County, including along its bike paths, at highway bridge abutments and in open areas along Newark Granville Road.

Boggs wrote in his online article that “the toxins must be ingested or enter through the eyes or nasal passages to induce poisoning.” And he said that while the plants are not known to cause skin rashes or blistering like some similar-looking noxious weeds, “this plant should not be handled, because sap on the skin can be rubbed into the eyes or accidentally ingested while handling food.”

There is another possible entry point that should be considered considering management options: its sap when aerosolized, such as when run over with a lawn mower or hit with a string trimmer – or even a chainsaw.

Boggs wrote that “a story titled, ‘Hiding in Plain Sight’ published in the ‘Life + Health’ section of Good Housekeeping (April 2022, pgs. 21-25) described a disastrous encounter with poison hemlock … in southwest Ohio. In May 2021, a landowner was using an electric chainsaw to cut down large weeds on his property,” and it turns out that it was poison hemlock.

The man was seriously ill and hospitalized for weeks, according to the magazine story.

Experts say the best way to manage poison hemlock is with a common herbicide, such as glyphosate, and to do it now while the plant is young, tender and low to the ground. A month from now, the plants will be taller than many humans.

Earlier this month, the Ohio State University Food, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Department published an article titled “Look for Poison Hemlock Now” as part of its “Licking County Agricultural News.” It noted that if not treated, the plant can reach up to 10 feet tall, giving it a very different appearance than its current carrot-like tops. And after it matures and blooms, it produces lots of seeds that allow it to spread.

Poison hemlock is listed on Ohio’s Noxious Weed list, which categorizes it as an unpleasant weed that one would not like to see sprout up in fields, pastures, and yards, but something that can be controlled by what the Ohio Department of Agriculture calls “good cultural practices.”

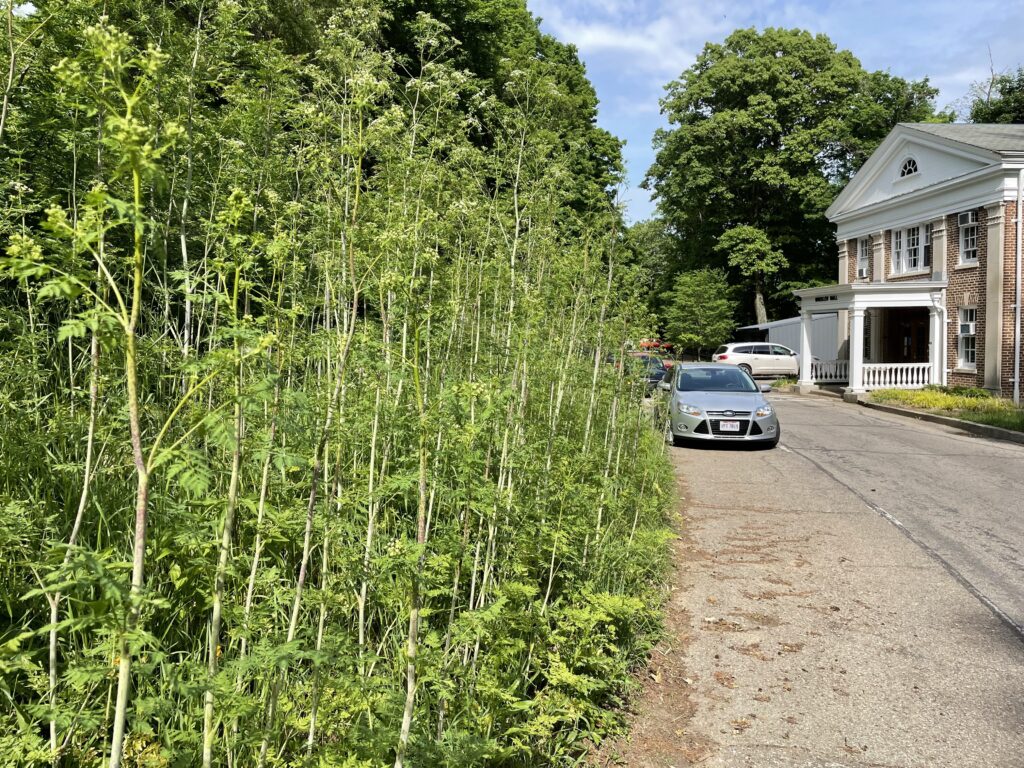

Denison University’s grounds crew is currently working to manage the plant before it blooms, as happened last year on campus. Large stands of the tall, mature plants were found near Whisler Hall and at other spots on campus.

Kevin Mercer, the Denison grounds and landscape services manager, knows how quickly the plant can get out of control. “From an invasive standpoint, I totally agree (that) it does need to be rectified,” says Mercer. “It can take over; it can take over a lot.”

Mercer and his team treat the plants with targeted use of the herbicide RoundUp, which affects only the plant it touches, preventing seepage into the surrounding grass and foliage.

Typically, the herbicide is sprayed in early spring as the seasons change. But Mercer said the timeline for poison hemlock removal “all has to do with temperature. When that temperature warms up, it’s like go time; you gotta react quick.”

Mercer and the grounds crew tracks the plants, and they have seen a 10% reduction in plants since last year, and they hope to see a greater reduction in the next three years due to their management plan.

“We try to be really good neighbors for the community, you know, and our campus community,” Mercer said.

Annie Kennedy writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of the Denison University Journalism program, which is funded in part by the Mellon Foundation. thereportingproject@denison.edu