On the Frontiers of Change

Bill Heinemann, one of the creators of the famous “Oregon Trail” computer game, has a funny story:

His daughter Marjie was on vacation in Iceland when she became so sick with diarrhea that she had to be hospitalized.

Doctors there rehydrated her, but struggled with a diagnosis. They flew her back to the United States for medical care, where she finally learned the bad news.

“You have dysentery,” he said. Dysentery is an infection of the lower intestine that is usually caused by contaminated food or water.

Marjie couldn’t stop laughing, her father remembers.

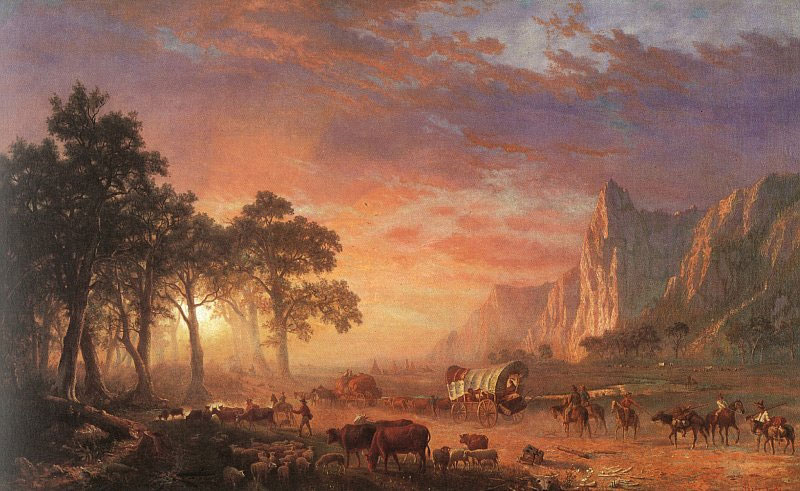

In the early 1800s, thousands of people started west from Independence, Missouri, on the Oregon Trail. They’d heard about new territory on the west coast and were looking for a fresh start on fertile land.

160 years later in 1971, three college guys in Minnesota pioneered a new “Oregon Trail”. Don Rawitsch was a history major and, while student teaching, started working on a board game to help his class learn about westward expansion. His game was spread out on the floor when his roommates Bill Heinemann and Paul Dillenberger came home.

Heinemann and Dillenberger were early computer geeks and saw an opportunity to put the programming classes they’d taken to good use. They were college kids looking for a challenge. After a couple weeks of late nights, the “Oregon Trail” game was finished. At least the first version.

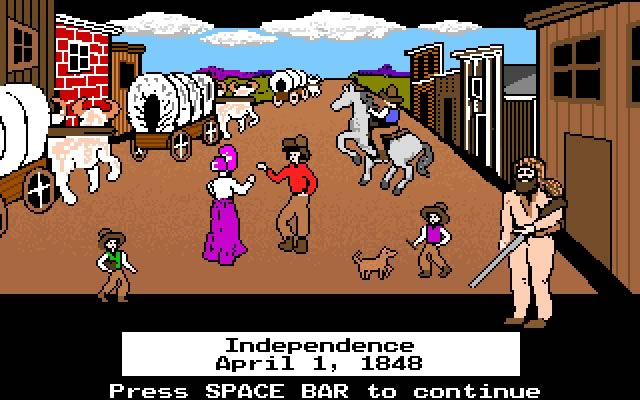

In December of 1971 they unveiled it in the class that Rawitsch was teaching. That early game was crude by today’s standards. There was no screen, for example. Students typed in their decisions and then the game typed back at them on a bulky teletype machine.

But the first players loved it.

The computer game simulated the trip to Oregon. It was based on real decisions and problems that the pioneers encountered. How much and what kind of food to carry? Oxen or mules? Ford the river, or caulk the cracks in your wagon and try to float across? Players can make all the right decisions and still not make it. There is snake bite, drowning, and cholera.

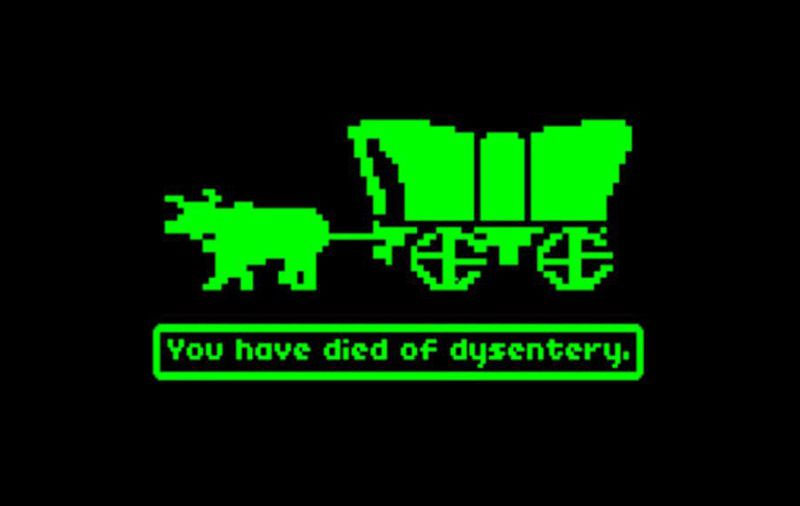

Or, most well-known of the tragic fates that could befall one on the road to Oregon, imparted in cold words on a dark screen: “You have died of dysentery.”

The gift shop at the National Frontier Trails Museum in Independence, Missouri, is filled with souvenir imitations of belongings that traveled with the pioneers along the original 2,170 mile trek to Oregon. A woman’s bonnet. A harmonica necklace. A buffalo purse.

The Oregon Trail, one of three major routes west, began in Independence, which at the time was perched on the edge of America. Every spring the city bustled with pioneers looking to stock their wagons before heading out on the open plains. People undertook the difficult westward journey for any number of reasons, some simply attempting to leave difficulties back east far behind. The key was to start early enough. The trip might take six months, and unseasonable winter snowstorms could be disastrous.

David Aamodt, administrator of the National Frontier Trails Museum, has watched the Oregon Trail story resonate with visitors for over 18 years.

“The story of the trail is not really the story of the paths they took, but the lives they changed,” he says. “They were ordinary people who simply wanted a better life. And because of what they did, they undoubtedly changed the world.”

The Oregon Trail migration was well-documented. Travelers’ letters and diaries recorded glimpses of life on the trail and sometimes even included tips for future travelers: when they should set out from Independence, and what they should be sure to pack and, more importantly, leave behind. Oxen eventually tired, and the sides of the trail were littered with writing desks, chairs, and grandfather clocks.

But these emotionally-valuable possessions often ended up not being worth their weight, as 11-year-old Lucy Ann Henderson Deady recounts in a letter on display at the museum:

“It was getting so late that…the men on the wagon train…decided to throw away every bit of surplus weight so that better speed could be made…A man named Smith had a wooden rolling pin that it was decided was worthless and must be abandoned.

“I shall never forget how that big man stood there with tears streaming down his face as he said, ‘Do I have to throw this away? It was my mother’s. I remember she always used it to roll out her biscuits, and they were awful good biscuits.’”

When Rawitsch, Heinemann, and Dillenberger thrilled those first students with their game, it was long before people would carry around computers in their back pockets. They weren’t even in most homes. But they were becoming more common in schools, and games like “Oregon Trail” demonstrated their potential to be both educational and fun.

The game stuttered through the next few years. Rawitsch got a job with the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC) in 1974 and took the game with him. Tweaks were made. In 1978, MECC accepted a bid from Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak to create software for the Apple II, the first widely popular microcomputer. More tweaks. More improvements. The Apple II version is where the phrase “You have died of dysentery” entered the game. And popular culture.

Ultimately the game was so successful that students born in the late 1970s and early 1980s have been dubbed the <a href=”https:https://socialmediaweek.org/blog/2015/04/oregon-trail-generation/>“Oregon Trail generation”.</a> By the 1980s, almost 5,000 school districts across America had received the Apple II version of the “Oregon Trail” game. And here’s the kicker: with the gigantic computer software market still off in the cloudy future, each district had permission to make unlimited copies.

“We’ve gotten a lot of fame, not necessarily fortune, from it,” Rawitsch says.

One of the most popular features of the game was that it allowed players to type their own name and to add names of their friends and family as their wagon party.

It wasn’t long before elementary-school wise guys saw the opportunity: “Potty face has died of dysentery.”

One person said on Redditt that he always played under the name “Dog Poop” because when his character died, the trailside tombstone would say “Here lies Dog Poop.”

There is a field across the street from the National Frontier Trails Museum. And in the field, there are swales–remnants of covered wagons and oxen digging through the earth. You’ve got to look hard to see them.

Actually, swales are more reminders than remnants. They are grass-covered and their ridges have been worn down over the years to the point that they are hard to pick out from the rest of the hillside.

“You didn’t see them, did you?” asks Richard Edwards, the museum’s former education coordinator. “They are very, very subtle. A swale is a rut that has been mellowed by time.”

There are more permanent markers along the trail. There are boulders where pioneers etched their names and the dates when they passed by. And in some places, the ruts are remarkable. Paul Dillenberger took a trip through Nebraska, and stopped at California Hill near the Platte River.

“I stopped at the marker, and you could actually see the wagon trail ruts,” he said. He has photos showing clear furrows going up the hill.

Forty-five years after it was created, the game has left its own marks.

Dillenberger sometimes works as a substitute teacher in his local school district. When word gets out that he’s one of the guys behind Oregon Trail, crazy things start happening.

“[Students] come up and want selfies with me and they want my signature,” he says with disbelief. “The number of people who had contact with the game worldwide, that’s mind-boggling to me.”

Ordinary people can have a big impact. And when it happens, folks don’t forget easily.

“A stranger rang my doorbell and asked, ‘Are you Bill Heinemann of Oregon Trail?’” Heinemann recalls.

In 2016, Rawitsch participated in the Reddit feature, “Ask me Anything.” He ended up staying online for almost two hours. Some two thousand people logged in to chat. Some made irreverent comments, but most just wanted to tell him what his game meant to them or to ask questions.

One commenter, with the handle “salad_dressing_dude,” confessed that when he was in grade school, he’d misread the famous “Oregon Trail” line as “You have died of dentistry” and just assumed that “dentistry was probably pretty dangerous back in the day.”

Others offered tributes: “Thank you for setting my life’s course,” typed OmahaVike, “[Oregon Trail] was the first “video” game I’ve ever played (can we call it that since there were no monitors?!?). I wound up with a BS and MS in CompSci and have a great career as a software dev. Just another human [on] whose life you have had great influence, and I really needed to thank you for this.”

Then, another question: “How are you not dead from dysentery?”

(Feeling nostalgic? Here’s the game on Internet Archive – Eds.)

Greg Bowers worked as sports editor for the Columbia Missourian and taught at the Missouri School of Journalism. He’s written essays and articles for a number of publications, including pieces for Missouri Life about rock icon Chuck Berry’s monthly shows in a St. Louis basement club, and an overnight at what could be the last all-night jazz room in America. His personal essays have appeared in the Southeastern Review and Saw Palm.