A Librarian on the Frontlines of a Changing Rural America

Lily is anxious, whining and barking at the slightest noise or movement. She’s waiting for the school bus to arrive. The elegant doberman stares longingly out a big glass window at the street. The front door of the Hartford Library keeps blowing open and shut, compounding Lily’s anxiety.

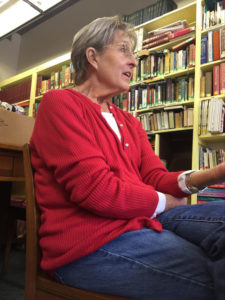

“The wind is coming due east and it keeps the door a-flopping,” librarian Faith Barker says.

Lily turns from the door and nudges Faith’s leg. She leans down and Lily licks her face. “Yes, ma’am. The bus is coming. Calm down. It will be here.”

It’s cold and there’s a dusting of snow on the ground. The gray Ohio sky shows no promises of spring, but inside this tiny library it’s cozy and warm, as it is every Tuesday and Thursday when the library is open. On those days, Faith organizes shelves and helps check out books, as most librarians do, but she also runs a food pantry every Thursday and stocks book bags and coats for kids.

The library feels lived-in, homey. It’s in an old bank, and there’s a walk-in vault in the back. Books are shelved and piled all over the place, almost haphazardly, except that Faith Barker knows where everything is, and she also knows her town.

Hartford is a speck of a town in central Ohio, a place that might make Washington Irving’s heart soar. Locals call it “Hartford Village” and it’s 402 residents take immense pride in the annual fair they host. The Hartford Fair is a real deal 4-H fair focused on raising livestock and filling kids full of sugar, where for $2 you can buy the biggest scoop of ice cream this side of the Olentangy.

Coffee, cocoa, and tea are always available in the library, but every Thursday Faith hosts a “Bread Basket.” The Kroger in Johnstown, just down the road, donates the day-old bread and she gives it out to anyone who wants it. She’s been doing this for over twenty years.

Faith started doing this, she says, because she could tell that some of the kids coming to the library weren’t well fed.

“Being a mom, or just a caring human being, you can look at these children and you can see hunger,” Faith says. “So I would talk to them and they were in the free and reduced lunch program and there was little to eat at home.”

Now, Faith says, people come for Bread Basket Thursdays from around the area. She gives the food away—no questions asked. There are a lot of people, she says, who you might think are doing well financially, “But when you really, really listen, you find out things are a mite tough. Of course there’s a lot of pride and I can’t fault that. We all have pride, and I don’t judge pride.”

(Full disclosure: Faith Barker insisted that I take a box of day old donuts. They were delicious.)

Faith also wants to make sure that the kids who pass through the library door are prepared for school. In the back of the library, in a dark closet near the furnace, she stores pencils, backpacks, and notebooks.

But her real work, it seems, is intangible. She loves the children who come through the door and treats them as she would her own. Some of them go home to empty houses, and Faith says she wants to provide a safe space for them, but more importantly she wants to encourage them to read, to learn, and to do well in school.

“I see report cards before parents sometime. I’m known as the town pusher. I push education.”

The Hartford Community Library does not receive state, federal, or local funds. They buy very few books and rely mostly on donations. They have a few computers and wifi for patrons—and, of course, coffee, tea, and cocoa. The library hosts a few fundraisers: they screen films on the town square, and in August they sell books at the fair for a quarter. Most of their funding is the result of a bequest from a patron who left the profit from the sales of crops of one tract of farmland to be equally divided between Hartford’s two churches and its library. It wasn’t enough to sustain the library, but it helped. Recently, profits from the sale of this land were transferred into a trust, and the library receives the annual interest.

Places like Hartford, where libraries are a significant public community space, face uncertain futures, in part because of changes facing rural America: dwindling populations, shifting demographics, and a loss of public institutions like schools, hospitals, and post offices.

While most rural libraries are locally-funded, a surge in anti-tax sentiment is putting that funding at risk in some places. The Koch Brothers-funded Super PAC Americans for Prosperity has targeted local library levies in Illinois, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Kansas. And the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS), an important source of federal grant funding for libraries, is threatened by the Republican Study Committee’s budget agenda from March 2016, which called for completely defunding the agency.

Susan Hildreth, Distinguished Practitioner in Residence for the Information School at University of Washington, and a former director of IMLS, says that federal funding streams are a perennial concern, but, “The bigger challenge is that some people don’t see the relevance of a public library because they can access information online. But so many decision makers haven’t been in one in so long. They’re remembering their junior high school library!”

Libraries serve as community centers, Hildreth adds, offering job training, free and reduced lunch in the summer, and programming for seniors.

And, in a place like Hartford, the community library is also a second home.

When the bus finally arrives, Lily pops up, jumping around and barking. The door opens and a young girl walks in and hugs Faith.

When the bus finally arrives, Lily pops up, jumping around and barking. The door opens and a young girl walks in and hugs Faith.

“How was your day? You look tired,” she says to a young girl.

“Yes, I am.”

“You’re not getting sick?” Faith asks.

“No.”

“Someone knows where you’re at?”

“Uh huh.”

“And you have homework? And you’re hungry?”

The girl nods.

“Go wash school off your hands and we’ll have a snack. It might be on your hands, but no sense putting it in your tummy.”

Faith has lived in Hartford for thirty years, and a lot has changed in that time.

“It’s not the same town as when we moved here. We used to have a pizza shop, a market, and a diner. Used to have two beauty shops—now only have one. If you go back a hundred years, the train went through. We had five gas stations. We had three mercantiles.”

In some ways, the town relies on the library as a place to see each other.

“A lot of the people don’t neighbor,” she says, using the noun as a verb. “The other major change is that the public school closed. When we lost our school, everything started to fall away too. But the library stayed.”

The library’s future, though, is also tenuous.

“What my vice president is concerned about is that we are getting older and who’s going to carry on?” Faith wonders.

It’s a good question because the things that keep places like this going are the people.

She pauses from our talking and tells a pre-teen heading for the door to zip up her jacket. The girl responds that it’s not that cold and she’ll be right back.

She pauses from our talking and tells a pre-teen heading for the door to zip up her jacket. The girl responds that it’s not that cold and she’ll be right back.

Faith raises an eyebrow and replies, “Okay, well, when you come back I’ll stick your chair out there on the street and you can do your work out there.”

Faith remembers a time when they first moved to town and her kids wanted to ride their bikes to the school. They were gone a few minutes and the phone rang. It was someone from the other side of town. ‘Mrs. Barker did you know your children are riding their bicycles in West Hartford?’

“And I said, ‘Thank you.’ And I meant it.”