As a child in South Carolina, my nightly ritual was to go into my parents’ room and tell them goodnight. They would usually be reading in bed, the television on low, waiting for the late news on WIS-TV. As I got older this became rather perfunctory—sometimes I’d just peek my head through the doorframe and say, “Goodnight.”

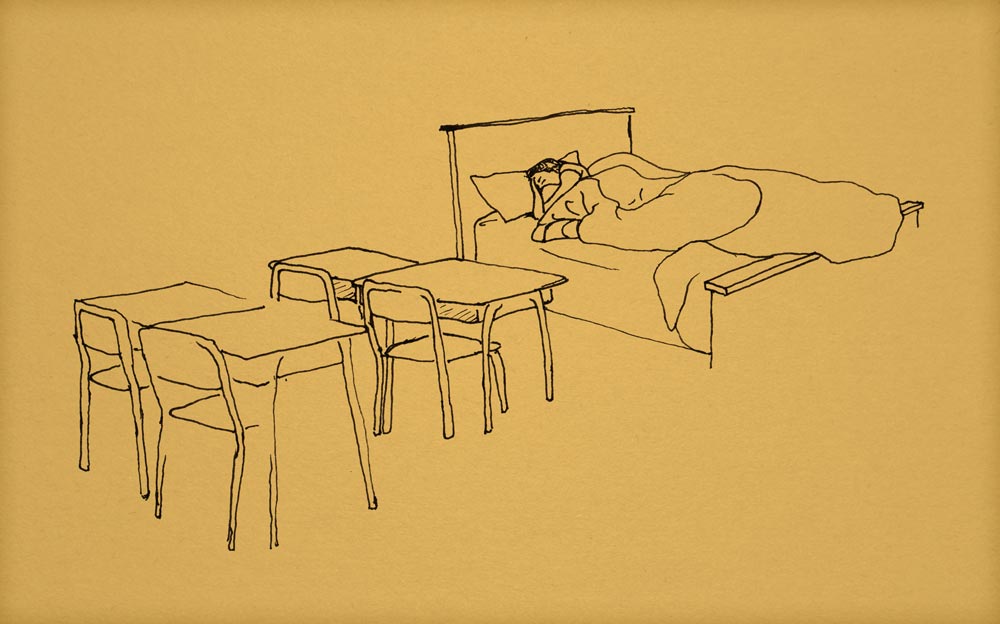

One night, maybe in seventh grade, I was in the process of this ritual when I noticed that something was off, that my mother was crying, her head on her pillow.

It was her first year as a guidance counselor, a second career after years as an English and French teacher and as mother to three lively children. When the South Carolina Department of Education mandated guidance counselors for every elementary school in the state, my mother went back to graduate school and got her Master’s degree. I had no idea what a Master’s Degree was, but it sounded impressive.

But then I saw her cry that night. It was the first time I’d seen an adult cry and it unsettled me. It was a moment of recognition and puzzlement—if she’s so upset, then who’s in charge?

The thing was, though, Jane Shuler was completely in charge. She was always in charge. In charge of the house. In charge of my education. In charge of discipline. In charge of manners. One time she berated me in front of the Belk Hudson for not opening the door for her. A woman walking by shouted, “That’s right, ma’am. You teach that boy some manners!”

She was also in charge of her career and of her own professionalization. For seventeen years my mother worked as a guidance counselor at Rivelon and Mellichamp Elementary Schools in Orangeburg. And then worked for three years implementing a positive-behavior intervention program in schools around the state. She taught conflict resolution, positive behavior skills, and even social etiquette. She took young girls to visit working women in the community, and dealt daily with the trauma faced by children living in poverty.

I’m guessing that’s what was happening that night—something had struck a cord. It must have been complicated to come home to a house with an actual white-picket fence knowing that her “other” children were going home to uncertainty.

I don’t know the details of that moment, but I do know that she gave a lot to that job. Her students and their parents loved her for that. To this day, a trip with my mother around town is akin to a red carpet walk. Everywhere she goes a former student, or the parent of one, recognizes her.

And yet, we live in interesting times. For decades now, it seems, the goal of many politicians has been to deprofessionalize education, to seize control of the classroom and the curriculum—to take the power out of the hands of capable teachers like my mother. The focus on testing, the low pay, and the micromanaging of teachers underscore a lack of understanding about what takes place in the classroom. In Ohio, Governor Kasich recently suggested that teachers do internships with business leaders so they can learn about the real world (though his proposal is now dead).

Tell that to my mother. Or tell that to all the educators who have been a part of my life—my friends, my sisters, my grandmother, my wife. Hell, tell that to my great great grandfather Reverend Virgil Wilson who was a pastor, a teacher of another sort.

In many respects, Rev. Wilson was a teacher, a professing man. The term profession or professional has religious origins—it has to do with vows taken to enter a religious order; it is a declaration of faith. Later the term was extended to medicine and even to the military.

Profession implies that your work is not simply a job but a career—something about which you have deep knowledge and, even, wisdom. Professionalization is not about closing out the rest of the world—it means that you have the skills needed to do specialized work. This is why unions require apprenticeships. This is why doctors go to med school.

And yet, increasingly, our culture doesn’t expect the same of teachers.

Jon Hale, Associate Professor of Education at the College of Charleston researches and teaches the history of education. Hale thinks we’re at a critical juncture for public education in the United States, reached in part because of the deprofessionalization of teachers. He cites the break-up of teacher’s unions, and the rise of Teach for America (TFA) and alternative credentialing programs, as two of the leading causes.

It used to be that teachers had to go to a college or university with a program accredited by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. In the 1990s, though, alternative route programs started popping up and exacerbated already glaring inequities. Now there are state level and even local level accreditors—in part, to make it easier to recruit teachers. Programs like TFA recruit recent college graduates who participate in an intensive five-week summer program, take graduate classes, and work alongside a master teacher. No doubt TFA lures some bright young people into teaching, but the program only requires a two-year commitment.

This worries Jon Hale. “The appropriate education of a student is only going to happen through the professionalization of the field of teaching,” Hale says. “If a child in poverty goes to school with social, cultural, and economic disadvantages, it takes an expert to work with that child.”

And, Teach For America, Hale says, lets America off the hook, offering a quick fix that keeps us from having to address the real issues of class and race, the fact that we don’t fund schools equally. Two years is not long enough for someone to become an expert, Hale says.

An expert teacher has the classroom chops and the deep knowledge that comes from schooling and ongoing professional development. I doubt that many of those who denigrate the teaching profession understand what it’s like to stand before a classroom and not only teach but share your love for a subject. Val Madsen, one of my teachers in graduate school at Brooklyn College, once told a classroom of young wannabe writing teachers that, “The key to teaching is to love your students. It’s that simple.”

In a way, he was correct. If you love them, they will make you practice patience and care and they will make you take your own professionalization seriously. That’s what makes teaching such a complicated profession—in the same way that the practice of medicine can be.

You are engaging with other humans. You enter a classroom and you have to quickly figure out the right way for a particular group of young people to learn in a particular moment. And then you must recognize that these young people have lives that are often painful, often tragic.

I don’t know exactly why my mother was crying that night. Guidance counselors and teachers in public schools are tasked with teaching but also with counseling and carrying the burdens of their students. During those years in public education she carried stories of violence, neglect, and abuse.

We ask our public school teachers to do a monumental task. At Mellichamp, where my mother worked for most of her career, 95.7% of students participate in some public assistance (Medicaid, SNAP, or TANF) and 92% qualify for free or reduced lunch. To work with with those kids—the kids who need it the most—to teach them, to support them, to love them, we need professionals.