I am grateful that the Knight Foundation and others are tackling the stark realities of technology’s threats to our democracy, and to journalism. Where goes one, so goes the other.

I have struggled with how to frame my remarks for the commission. Because I wanted to speak—not just as a journalist—but as a digital citizen.

At the moment, my love affair with technology is waning… But please realize I have enthusiastically been an early adopter going back to 1984. In the mid 90s, I was all in on the Internet’s promise to right injustices, to insert missing voices into democracy, and to bridge divides.

In the late 90s, I worked with colleague Joel Beeson to do a first-wave multimedia community workshop in Pickens County, Alabama, where we climbed up a telephone pole to jerry rig access to dial-up internet next to a trailer with no water and using electricity from a generator to power a donated bank of computers.

Look at us, we thought. We are winning this technology game.

Now I am the director of an innovation center where we do mixed reality and AI. We even have a brain-computer interface lab. Blockchain. Bot building. All the things. Technology is my job and has been for a very long time.

But we are not winning.

My partner studied with Internet pioneer Phil Agre at UCSD in the mid 90s. Agre’s work included the piece “Surveillance and Capture,” among many other writings about the dangers to come in our digital worlds. Agre, a proto-inventor of the social web, grew increasingly worried about the consequences that communication technologies would have on society. Then In 2009, he mysteriously went missing— he abruptly left his job and disappeared off the grid.

Today that act resonates. Not because we are naïve about technology. But because we understand it all too well. “It’s time to go Phil Agre” we often say to each other now.

Because in addition to being colleagues who have long worked in this space, we are doing our damnedest to parent 11 and 12-year-old boys for whom the pull of ubiquitous technology outpaces our 1000s of hours of controls, restrictions and interventions. While they own no devices, their friends do. And we are also subject to the very Chromebook-for-every-child mandate we once evangelized and wrote grants for to bridge rural divides — while recent evidence suggests it has little benefit on learning outcomes — but on which appalling content is available despite every filter — content that no platform, institution or agency is liable for, thanks to the slippery safe harbor amendment that only makes the internet safe for technologists and their shareholders.

Platforms like Instagram intersperse feel-good memes with horrific anti-Semitic and racist memes. This unregulated soup of banality is an ideal medium for manipulative content in which white nationalists and other bad actors target our youth, our communities and our democracy. Neo-nazi YouTubers hide in plain sight with millions of views: “Just a prank bro.”

We are not winning.

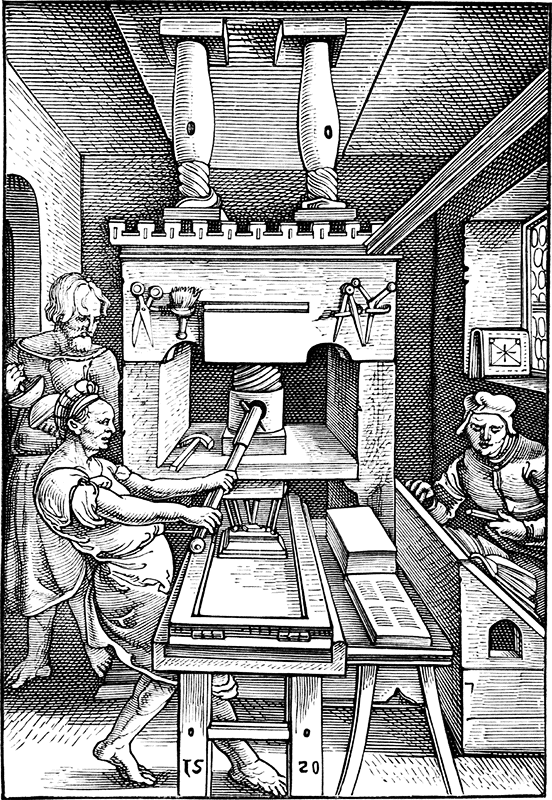

Wikimedia commons

Wikimedia commonsAt 100 Days in Appalachia we’ve launched an investigative project on the tactics white nationalists and other actors deploy on social media to target underserved young men in rural communities in Appalachia.

Meanwhile journalists mostly talk to each other about what fresh hell has befallen the industry — and despite our best efforts to tech up and prototype our future, we still have minimal influence in the technology sector. And we are caught unawares, even bewildered, that truth itself has been disrupted.

But if innovative disruption is the arrival of an inferior product that serves the needs of an audience unmet by established players…. Welcome Steve Bannon and Breitbart, Alex Jones and Infowars, sub-Reddits, 4chan and legions of bots more clever at community building than we dared to be.

We can, like all incumbents do in disruption scenarios, hold our noses and cast disdain on the inferior products. Or we can look in the mirror. And cop to our own narcissism that we alone know what’s best for journalism or democracy. And we can dispel the delusion that the technology giants have been our allies while we’re at it.

We are not winning.

Wikimedia commons

Wikimedia commonsAs an Ozark girl meets Appalachia, I have watched the shift over a decade in my Ozark-origin feeds. A rise of politicized false news and populist memes making the rounds, becoming ever more overtly racist, corrupted and revelatory about who we are as a nation: polarized and ill-informed. I watched as Sandy Hook conspiracy theories proliferated—not by a lunatic fringe—but by school teachers, soldiers and cops and daycare workers and nurses from my small town. But who also, I noticed, often struggled with healthcare and shared stories that revealed their lack of access to affordable care. And sure enough, right along with their conspiracy news they posted streams of alternative medicine stories and links to quack products. All of it fake news — but also classic disintermediation of establishments that had long been beyond their reach…and in whom their trust had steadily eroded.

I could delve into my frustrations as a journalist with Facebook and other platforms — where journalists are more like sharecroppers than publishers, content farming on someone else’s property for someone else’s gain — but I think you can guess where I stand.

Recall, I have spent years trying to access the technology table. Courting Facebook and Google. Really…it was a love affair on my part. But an unrequited one.

Now, I don’t believe technology is the right tool to solve a technology problem.

My current pessimism about technology has been replaced with optimism about journalism. In fact, I think publishers should have the guts to ‘go Phil Agre’ on Facebook.

Democracy needs Journalism more than it needs Facebook.

And Facebook needs Journalism more than we need Facebook.

But only if we act collectively…and act locally.

I did a “mobile mainstreet” project in the early 2000s. It was designed to wrest distribution of local information away from what was then a young Facebook in an effort to maintain distribution paths by way of the local newspaper. At that time local businesses were frustrated and suspicious about social media and didn’t know how to build an audience and still wanted their local newspaper — also their friend and neighbor — to help them do that. I guess that project was a failure — I mean we didn’t exactly disrupt Facebook…but I also haven’t given up on the idea that local news, with the right platform, can lead in the local social space with more trust, reach and impact than Zuckerberg.

And it’s why we started 100 Days in Appalachia. Sustaining the future of independent coverage from local media in our region’s and countries’ smallest communities has never been more important or more opportune. We’re also working with our state press association to help journalism entrepreneurs buy dailies and weeklies to seed new digitally savvy owners of local newspapers — and to do the hard, on-the-ground, face-to-face work of trust building in a community. Homesteading journalism, if you will.

And we’re not doing all of this because we think local news needs saving.

We’re doing this because we think local news can save us.