After an hour and a half of discussion by three presenters about the impact of the Intel project and data centers being built in western Licking County, questions came rapid-fire from the more than 40 people attending a town hall meeting 3 miles from the Intel campus.

What chemicals does the company use or emit? Could they get into the air and water? How dangerous are they? Could they explode?

The biggest concern right now, said presenter Madhumita Dutta, an assistant Professor of geography at Ohio State University, is the unknown.

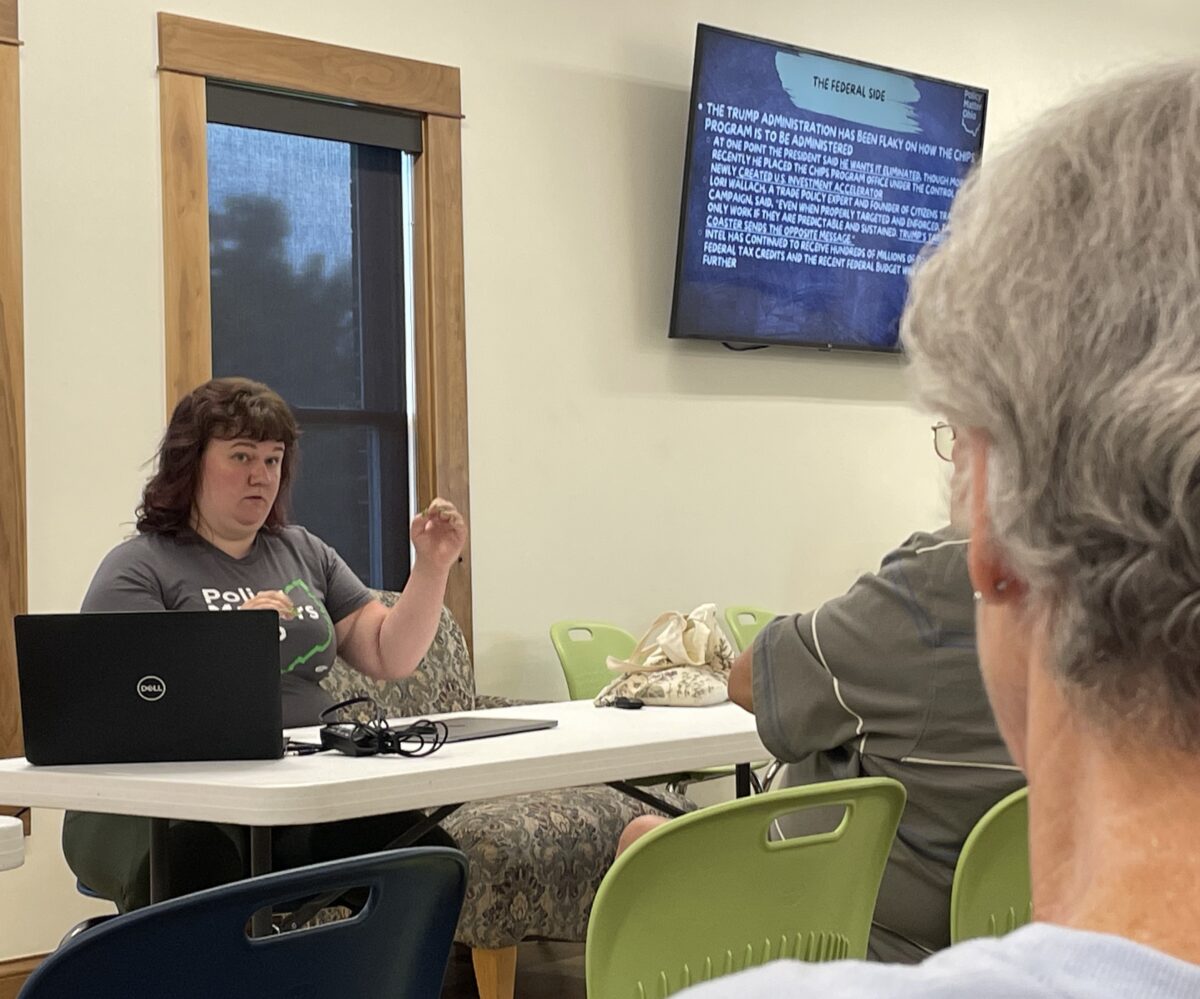

“It’s not so much that they will explode, but that we can’t see them,” she told the audience at the Mary Babcock Public Library in Johnstown, which was the site of an informational town hall meeting hosted Aug. 13 by Policy Matters Ohio and the grassroots Clean Air & Water for Alexandria and St. Albans Township.

And by “can’t see them,” Dutta was referring to agreements by government officials and agencies – including the Environmental Protection Agency – to shield the specific details about the chemicals used in computer-chip manufacturing from public view based on corporate concerns about revealing trade secrets.

Intel announced in January 2022 that it would come to Ohio. It is now building what it said would be a $28 billion computer-chip manufacturing campus on the southern edge of Johnstown, a Licking County city of about 5,400 residents. The site is on former corn fields that were annexed by the City of New Albany as part of its international business park.

Construction has slowed as Intel has faced financial stresses. The company has said it will lay off 25,000 of its more than 100,000 employees worldwide this year – after laying off 15,000 last year – and announcing that it would delay its anticipated production start date in Ohio from 2025 to 2030 or later.

In addition to questions about the company’s future, and potential environmental effects, there are now concerns about the millions of dollars in state and federal incentives given to Intel to lure it to Ohio, said Bailey Sandin, of Policy Matters Ohio, a nonprofit organization that advocates for good government, fair wages and workers’ rights, public education and a clean environment.

She said the state has provided $600 million in grants to Intel and is spending approximately $400 million on infrastructure to support Intel. Another $300 million in state funds have been allocated for a water reclamation facility.

And the federal government pledged $1.5 billion for the New Albany project in the CHIPS Act approved by Congress in August of 2022.

Sandin said it’s possible the state could seek reimbursement of the $600 million if Intel facilities aren’t completed by the end of 2028, but she was skeptical that the state would do that.

In discussing the environmental impact, which was the majority of the presentation, Dutta said that key concerns are the potential release of hazardous gases and the industry’s use of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as “PFAS” and “forever chemicals,” which are currently unregulated by the EPA and are known to be harmful to human health. They also are known to make their way into surface water and biosolids, she said.

“All of these chemicals have the potential to contaminate our air, water and bodies,” Dutta said.

She said it’s possible to learn from the experiences of people who have been living near computer-chip manufacturing facilities that have been operating for decades in other locations, such as Arizona, California, New Mexico and Oregon.

One lesson is to get a baseline reading of environmental conditions now, before anyone starts making computer chips in western Licking County. A group of volunteers is doing that now by soliciting donations and building small air-monitoring devices. Ten of the devices have been deployed between Johnstown and Newark, and another 20 are available to be deployed, said Ken Apacki, who is leading the air-monitoring effort by the Clean Air & Water organization.

“We want to place monitors at places where you’d find vulnerable people – schools, libraries, nursing homes, fire stations and other public places,” he said, adding that he wants to have the remaining 20 monitors – and more, if more donations come in – by the end of this year.

He said he is also looking for volunteers to collect and analyze data from the monitors. “A teacher has volunteered to talk with schools about making this a citizen science project,” said Apack, who can be reached at kenapacki@gmail.com.

Collecting data now via the monitors that report data to the publicly available website www.simpleaq.org will establish a record of the current air quality – before Intel begins production and as data centers are built.

The concerns about data centers is that they often include diesel or natural gas-fired generators for backup power in case of an electrical failure, and some are building their own on-site, off-the-grid power plants that will run full time to power computers in the data centers. Burning fuel for power generates emissions and environmental concerns, he said.

Alan Miller writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism program, which is supported by generous donations from readers. Sign up for The Reporting Project newsletter here.