Susan Reid looks on as two children in front of her fight for control of a life-sized, red and white, single-engine Cessna 180 model airplane, iconic to those who recognize it.

The airplane is part of a display on the second floor of The Works, an interactive museum of history, art, and technology in Newark, Ohio.

With a slight smile, Reid turns to face the children’s approaching parents.

“Do you know who was the first woman to fly around the world?” she asked. “Her name was Jerrie Mock. She was my sister.”

Becoming Jerrie Mock

By the time she was 7 years old in 1932, Newark native Geraldine Mock knew two things for certain: She hated the name Geraldine, and she wanted to be a pilot.

So, she all but changed her name to Jerrie, and, after high school, began attending The Ohio State University where she studied aeronautical engineering — the only woman in her class. As was common at the time, Jerrie soon left her studies behind to settle down and start a family.

Her husband, Russell, was a pilot, and Jerrie began flying lessons at a small airport in Columbus in 1956. She received her pilot’s license two years later.

By 1962, she was a mother of three, tending to her children and managing the home.

Before Russell left for work in the mornings, Mock would ask him where he wanted to go for dinner that night. He would name a country, and Mock would spend her day preparing for that night’s destination.

Reid recalled Italian night — complete with a checkered tablecloth, a bottle of wine and candlelight — and another night where they sat on the floor around a low table complete with a bonsai tree and ate their meal with chopsticks.

“Even as a little girl, I was always so entranced by her,” Reid said. “She was so different.”

While she was fixing breakfast, lunch, and dinner and maintaining the family home, she managed to log about 750 hours of flight time. But she was restless.

Sitting around the kitchen table, Mock complained of how bored she was with her life. It was December, 1962, and her husband responded: “If you are so bored with your life, why don’t you just get in the plane and fly around the world?”

“Alright,” she said.

And that’s what she did.

Around the world in 29 days, 11 hours and 59 minutes

At the time, Mock only had six years of flying experience, but was determined nonetheless.

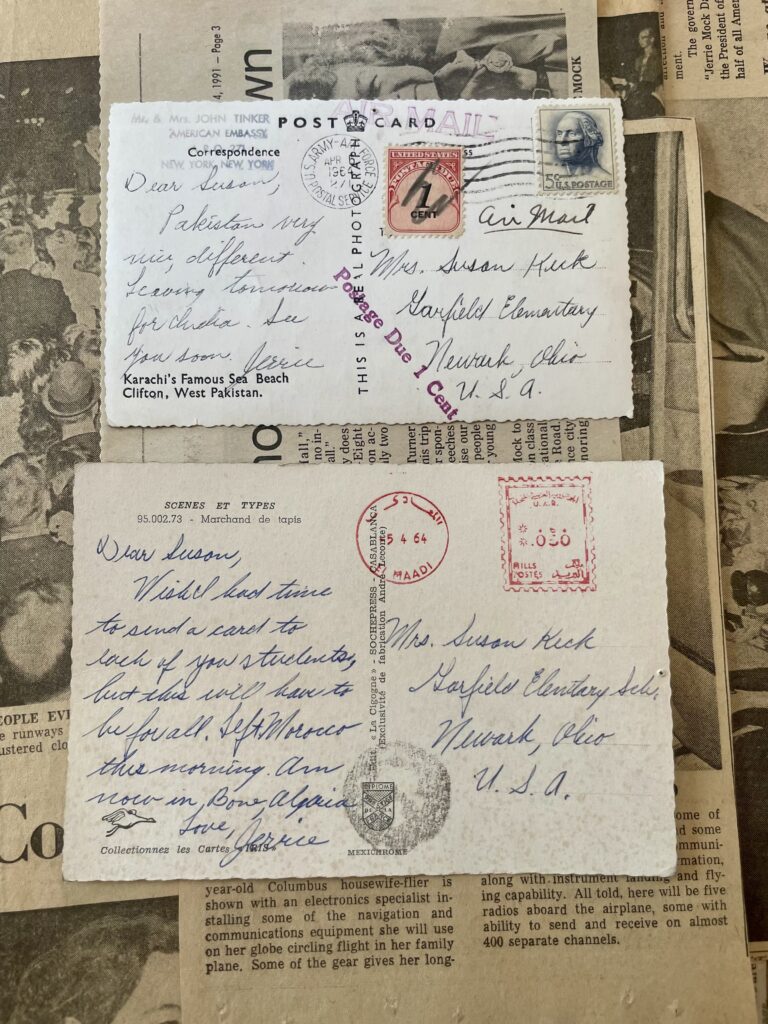

Her plane — The “Spirit of Columbus,” though she affectionately called it “Charlie” — underwent necessary modifications. Mock added long-range communication and navigation equipment, and tucked in her typewriter so she could keep notes and write letters to her family and articles for The Columbus Dispatch. In all, it took her over a year to prepare for the journey.

On March 19, 1964, she left Columbus and headed toward the skies.

Two days earlier, Joan Merriam Smith — another female pilot attempting to circumnavigate the globe like Mock — departed from Oakland, California. The pilots had planned for every obstacle they might encounter in the skies, but hadn’t anticipated the challenge of a race.

“Race? I hadn’t counted on a race when all this started. But suddenly I had competition,” Mock wrote in her 1970 autobiography “Three-Eight Charlie.”

A reserved and introverted person, Mock was not fond of the flashing cameras and news reporters that pestered her at every stop, asking questions about Smith and her progress.

“How could I politely make them understand how nervous they made me, explain that the prospect of flying single-engine over the oceans wasn’t nearly as frightening as crowds of people?” she wrote.

Mock had never set out to be on the cover of newspapers and magazines or to be dubbed with the infamous nickname “the flying housewife.”

She was never in it for the fame and glory of being “first.” Rather, she had what Reid called “the bug:” a desire to travel, a goal to see the world, and a plan to fly an 11-year-old, single-engine airplane around the world.

Mock wanted to experience as much of the world as she possibly could, flying through poor weather and equipment failure to reach Bermuda, the Azores, northern Africa, the Middle East and beyond.

In “Three-Eight Charlie” she wrote about her frustrations after landing in Guam. Russell wanted her to rest for the next leg of her journey, but “I didn’t want to go to bed. I wanted to go swimming,” she wrote. “And I didn’t care at all about the history books. The people at Guam were much more fun.”

Mock landed back in Columbus on April 17, 1964: 29 days, 11 hours and 59 minutes after she departed. She was the first woman to complete a solo flight around the world.

Mock’s legacy

Katharine Chisolm, the communications and social media manager at The Works, is the current expert on all things Jerrie Mock.

While away at college, Chisolm got a call from her dad.

“Do you know who the first woman to fly around the world was?” he asked her.

Ashamed, she replied that she didn’t. “Well, it’s this woman named Jerrie Mock. And she’s from Newark.”

Chisolm attended the 50th anniversary of Mock’s landing in 2014 and has been flying high off of her legacy ever since.

Radio malfunctions and bad weather conditions made the 29 day journey back to Columbus hard, but the reward thrilling. By the time she had landed back in her home state, Mock had made 21 stops, traveled over 22,000 miles, and become the first woman to do it.

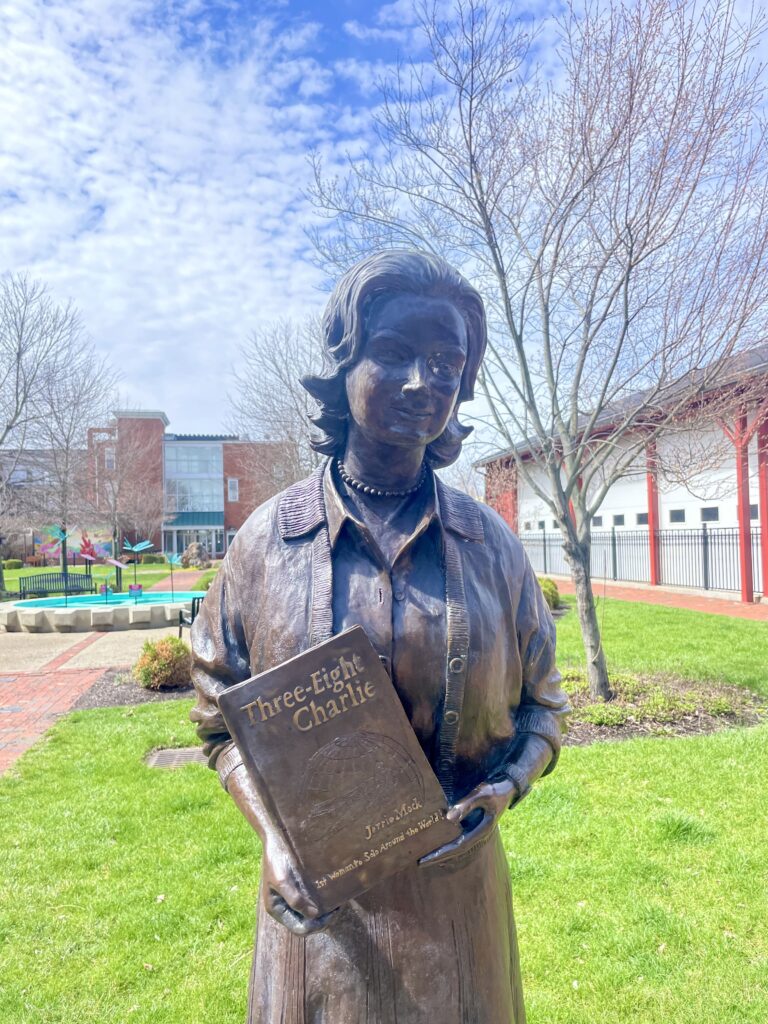

Her journey has become an inspiration to so many who have stumbled upon it, wondering who this five-foot-tall woman wearing a blue sweater and skirt is, the pilot with pearls circling her neck and high heels on her feet.

The ‘60s in America were a tumultuous time, and word of Mock’s historic accomplishment burned out quickly. In 1970, her autobiography was published, and only 1,000 copies were printed.

Wendy Hollinger, the owner of Phoenix Graphix Publishing, first heard about Mock at a meeting of the Experimental Aircraft Association. After hearing about the scarcity of her autobiography, Wendy and her partner, Dale — a pilot and airplane mechanic in the Air Force — flew to Quincy, Florida, where Mock had retired.

While visiting, the pair collected 825 photographs of Mock’s flight documentation, placing every piece of imagery in chronological order upon returning home to Granville. In 2014, the duo published a new version of Mock’s “Three-Eight Charlie,” complete with maps of her route, newspaper clippings, telegrams, and more.

“It is so important for us to acknowledge those heroes that come out of our own small towns,” Hollinger said.

The 60th anniversary of Mock’s record-breaking flight will take place on April 17. The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., will host an in-person and online event about Mock’s legacy with Hollinger and Shaesta Waiz, an Afghan-American aviator who Mock mentored.

The Works is planning an anniversary celebration on May 4, complete with an art gallery exhibition in her honor.

“I truly believe everyone has a story,” Chisolm said. “She has a story that was lost and deserves to be told, and she deserves to be remembered.”

Mock passed away in September 2014, and Reid still gets choked up talking about her big sister.

She sifts through possessions she has collected over the years, including photographs and letters signed with love from Mock. Reid places them back exactly from where she lifted them with such tender care, they look as if they haven’t been touched at all. Reid spends hours of her time spreading her sister’s name and story, hosting talks and giving presentations.

And everywhere she goes, she stops people to ask: Do you know who the first woman to fly around the world was?

This story was updated at 4 p.m. Wednesday, April 17 to correct the name of the Experimental Aircraft Association.

Annie Kennedy writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation and donations from readers. Sign up for The Reporting Project newsletter here.