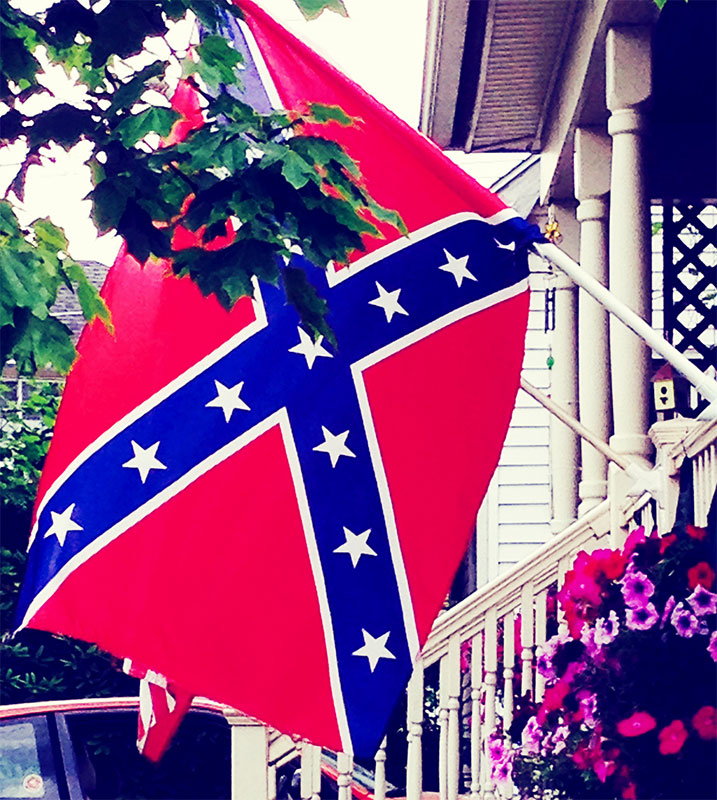

In Newark, Ohio, birthplace of Johnny Clem, the little drummer boy of the Union Army, Shirley’s neighbor is flying a Confederate flag next to his front door.

Shirley (not her real name) is African American and says it makes her nervous. She grew up in the South during Jim Crow, and says she’s sad to see that flag coming back.

Shirley says her neighbor came over to her house once, to attend a block meeting after some neighborhood kids kept revving their car engines late at night. He seemed nice, she says, but she hasn’t spoken to him since that flag went up. She wants to say something to him about it, but she’s not sure she ever will again.

“It’s the parents, this older generation keeps it going,” she says. “White people need to read more about the culture of black people; we built this country just like they did.”

“I saw a man yesterday,” she says, “with two American flags and one Confederate flag on his truck. I hadn’t seen it much until recently, until those people were killed in that A.M.E. church in Charleston. Some of them don’t even know why they’re flying it.”

The so-called Rebel flag, long a source of controversy, has become almost toxic since photos circulated of Dylan Roof–the young man who massacred nine people at Charleston, South Carolina’s Emmanuel A.M.E. church–standing in front of it. The flag was removed from the grounds of South Carolina’s state capitol where it had flown since the early 1960s.

Shortly after South Carolina took the flag down, Wal-Mart, Amazon, Sears, and eBay announced that they would no longer sell Confederate Flag merchandise. A man in Mississippi was so outraged by Wal-Mart’s decision, he set off explosives in a store. Meanwhile, public school officials in Kansas, Illinois, Indiana, and Virginia, among others, have asked students not to wear clothing displaying the Confederate flag.

In response to all this furling, pro-flag supporters organized rallies and protests across the nation from Oregon to Michigan to Florida. Some of these defenders call themselves “flaggers” and travel in caravans with flags waving proudly. Sometimes their efforts are fairly mundane, such as organizing Facebook groups to raise awareness. At other times their actions are more malicious: flaggers in Douglassville, Georgia were charged with making terroristic threats after driving by a black child’s birthday party and harassing party goers.

Despite the efforts of major retailers, Confederate flag sales are up. A representative from Ultimateflags.com, who would not give his name, told me sales of the flag increased in July 2015 and haven’t let up. During the summer of 2015, he says, “it was ridiculous.” They sell Confederate flags all around the world—as far away as Australia.

Given Ohio’s history, maybe the presence of the Confederate flag in the Buckeye state shouldn’t be surprising. During the Civil War, the Pro-South Copperhead movement was strong here, and tensions between pro-South and pro-Union groups were heated—especially along the Ohio River.

Ohioan Shawn McDonald flies a Confederate flag alongside an American flag on the back of his truck. He thinks more people are flying the flag because some stores stopped selling it and because “they’re trying to make a law where people can’t fly it.”

Ohioan Shawn McDonald flies a Confederate flag alongside an American flag on the back of his truck. He thinks more people are flying the flag because some stores stopped selling it and because “they’re trying to make a law where people can’t fly it.”

“I’m not racist,” he says. “It was a flag used for a battle and it means freedom of speech. It wasn’t a flag for slavery—it was a fight for land.”

It’s a myth, he believes, that the Confederate flag is racist. Besides, McDonald says, people give him the “thumbs up” when he drives around town.

And yet, the Confederate flag came back in the mid-20th century when followers of the Dixiecrat party waved it, thus linking it to pro-segregationist sentiment. Georgia added it to its state flag in 1956, and in 1963 Governor Wallace flew it over the capitol on the day Attorney General Robert Kennedy was to meet with him to discuss desegregating the University of Alabama.

More recently, Confederate flags were spotted at Donald Trump campaign rallies in Maryland, Virginia, Indiana, Florida, and elsewhere. At a Trump rally in Greensboro, North Carolina, last spring, two men posed with a Confederate Flag on which was written, “Trump 2016.” Donald Trump, Jr., speaking to a crowd in Mississippi, said the flag didn’t bother him, “There’s nothing wrong with some tradition.” Stephen Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist and founder of Breitbart News, published an article entitled “Hoist It High and Proud” in the weeks following the Emmanuel A.M.E. murders.

Shirley’s neighbor John says he doesn’t really care what his neighbors think about his Confederate flag. He has been flying it ever since South Carolina took it down and has no plans to stop.

“I just like the flag, how it looks. It made me mad when they took it down. I was gonna get one a while back and then that guy killed all of them black people in that church and I decided not to. But then South Carolina went and took it down. For all those years it was flying and they took it down?”

Half of John’s family lives on the South Carolina coast. “You know,” he says, “they’re real nice down there.”

“Who you like in the presidential election?” he asks, at that point we were knee-deep in the primaries.

“In all honesty, I’m not sure yet,” I reply.

John replies, “Well, I like Trump. He don’t bullshit. He don’t lie. He tells you what’s up.”

A shock of gray hair and a goatee frame John’s big grin. His arms are covered in intricate tattoos of crosses and angels.

A shock of gray hair and a goatee frame John’s big grin. His arms are covered in intricate tattoos of crosses and angels.

“It’s not racist. That flag symbolizes freedom.”

“But,” he continues, “I was told growing up to not like certain people. Again and again I was told that. I got a niece and a nephew who are half black and that has changed things for me. I’m working on that.”

At first, no one bothered him for flying the flag. But one morning he found the flag pole bent and on the ground.

“They did it about eight or nine times. So I went to Home Depot and got a steel pole. They haven’t been messing with it since then.”

A few months after I first spoke to Shirley, I followed up and asked if she’d spoken to her neighbor about his flag yet.

She said she hadn’t–the flag just makes her too nervous.

Jack Shuler lives in Ohio and is the author of three books including The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Christian Science Monitor, Salon, Truthout, and The Plain Dealer, among others. He teaches at Denison University where he chairs the Narrative Nonfiction Writing concentration.