Charles P. Henry had bad news for Denison University’s class of 1996 graduates: They weren’t going to change the world – at least, not as much as they thought they might when they were 18 or 21 years old.

It’s an atypical message for a commencement speaker, though Henry – who graduated from the same university in 1969 – had his reasons for saying it.

“The secret,” he told them, “is that the challenge and the reward are in the trying.”

About 30 years prior to his commencement speech, Henry was finishing up his first year at Denison University.

As a freshman in 1965, Henry’s experience at the university was shaped by racism. He was the only Black male student on campus, and there were no Black professors. There was the time he was warned that dating a white woman would cause tension on campus, and the time an economics professor told him he’d need to work “twice as hard” to succeed in his class.

Greek life dominated the social scene at Denison in that era, and some fraternities upheld national bans against Black members – though Henry rushed anyway. All but one of the fraternities rejected him.

Later, there was the time he and his wife were lied to about the rental status of a home in Granville.

Black-led African studies at Denison

Henry signed up for an African history course at Denison as soon as he saw it was being offered. He was excited for it, too. When he attended Newark High School, just a few miles down the road, he never got to learn about that subject.

But a few lectures into the course, he came to a stunning realization: His professor was arguing that colonialism was a good thing for Africa. Even African history at Denison was taught through a white lens.

Henry, the only Black student in the African History course, decided that if his professor wouldn’t teach the truth, then he would.

Henry offered a course called “Recent African History,” without the whitewashing, in Denison’s new, student-run experimental college.

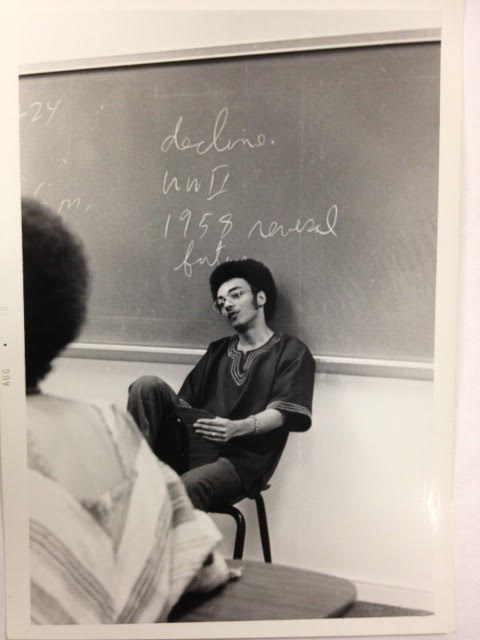

He got up in front of about a dozen peers to give lectures on the topic. He was nervous, realizing that he was only “a book or two ahead” of the students. But he had taken it upon himself to learn enough to teach the course through an Afrocentric lens.

Path to activism

On Feb. 1, 1960, four North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College students protested segregation at a local lunch counter. In the following days, a few hundred other students followed their lead.

Inspired by the Greensboro sit-in movement, college students all around the country started staging peaceful protests at segregated establishments. By summertime, restaurants across the South started integrating.

Back in Newark, a 13-year-old Henry was paying attention to the movement, as well as John F. Kennedy’s election to the presidency. Henry could sense that things were changing. At that young age, he made two important decisions: He would get a doctorate degree in political science, and he would push to improve conditions for African Americans, just like the students partaking in the sit-in movements.

Five years later, Henry enrolled at Denison. He had been drawn to the school after a political science professor named Fred Wirt invited him to visit campus as part of an effort by some faculty members to integrate the school.

Henry’s undergraduate timeline aligned with the start of the national Black Power movement. College campuses around the country were following the movement and taking action.

In November 1968, the Black Students Union at San Francisco State College started a five-month strike, which led to the creation of the first Black Studies program in the United States.

Progress, in terms of creating a more diverse and inclusive campus, was minimal at Denison throughout much of Henry’s time as a student. There were only about 13 Black students enrolled at Denison when his junior year started in the fall of 1978, as he recalled in a 2017 article titled “Black Studies and the Democratization of American Higher Education.”

The other Black students had similar stories to Henry regarding racism in and outside of the classroom. Black perspectives were not considered in courses, a problem encapsulated in Henry’s experience with the African history course.

It was time for change.

Henry and his Black peers began having conversations about their frustrations with Denison’s white-centric curriculum. These conversations prompted them to connect with faculty members who respected their frustrations.

In the spring of 1968, the students and faculty members collaborated to design a course called “Black Culture in America.”

The next semester, English professor William Nichols led the course on Monday afternoons and Wednesday evenings. Class texts included The Story of Jazz by Marshall Stearns, Negro Politics in America by Harry A. Bailey and American Negro Poetry by Arna Bontemps. Guest speakers like then-Indianapolis Mayor Richard Lugar, a Denison graduate who went on to become a U.S. senator, and Reverend Joseph Washington, a Black religion scholar, gave lectures to class members in Fellows Hall and Swasey Chapel.

Though enrollment was supposed to be capped at 20, it soared to 67 students packed into Slayter Auditorium for class discussions, including all 13 Black students. Four faculty members volunteered as discussion leaders.

The course covered topics that would later become backbones of the Black Studies Department: “the history of slavery, the crisis of the inner city, the development of jazz, Black theater and literature, economics of the ghetto, Black politics, and religion,” as Henry recalls in his 2017 article.

Still, the class was overwhelmingly white. Nichols and the volunteer assistants were also white. Black students found it frustrating that a white faculty determined their grades, especially since Nichols and his colleagues had acknowledged that they didn’t study the subjects they were teaching much in their own college and graduate school days.

Henry, the teaching assistant for the course, played mediator between the students and Nichols. At least one student came to Henry and said that they didn’t feel the need to study for the course, since they already had life experience as a Black American. Henry persuaded the student to take the class as seriously as they would any other course. Similarly, when Black students considered rebelling against the course’s grading system, Henry convinced them to give ground.

Saving grace

In 1976, Henry got a call from Lou Brakeman, one of his old political science professors.

Brakeman, serving as Denison’s provost at the time, had a favor to ask of Henry: Come back and bolster the Black Studies program.

The program – one of the earliest of its kind in the United States – was founded in 1970, and like most others at colleges around the county, was still finding its footing.

National program standards were ambiguous. At Denison specifically, a nonacademic was leading the program, which played into a stereotype of the time: that Black Studies was not a true academic field.

Henry, who received a doctorate in political science from the University of Chicago two years earlier, could change the narrative at his alma mater.

Henry and his wife, Loretta, had adopted their first child the same week he got the doctorate. Intrigued by the thought of returning home to his parents and in-laws with a grandchild, Henry took the offer. He would direct the Black Studies program and teach political science.

Once at Denison, Henry sensed tension between the Black Studies program and the Women’s Studies program. Both were new, interdisciplinary fields competing for academic relevancy.

Instead of trying to gain an edge, the new department director decided to build a bridge.

At the time, both programs were pushing for a general education requirement in the Denison curriculum. The prospect of either getting their wish was grim.

But Henry approached Women’s Studies department leaders with an idea: Propose a general education requirement for all students to take either a Black Studies course or a Women’s Studies course.

The proposal was approved. Even progressive schools like the University of California-Berkeley, where Henry would later teach, did not have such a requirement at the time. It predated the “power and justice” requirement in Denison’s current general education curriculum.

Henry also built bridges off campus. He connected the program with the National Council for Black Studies, which helped set program standards at Denison.

In addition to pioneering Black Studies at Denison and later the University of California-Berkeley, Henry served on the National Council on the Humanities for six years after being appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1994, chaired Amnesty International U.S.A.’s board of directors from 1986 to 1988 and currently chairs the Center for Victims of Torture’s Board of Directors. His tenth book, Racial Imagination and the American Dream: The Peacemaker, The Profit and the Politician, was published in August.

The days of overt segregation in academic institutions are well past, but discrimination – especially on the basis of race – still persists. In 2021, he FBI recorded 11,634 hate crimes in the United States, 3,421 of which were directed at Black Americans. Of course, in addition to these instances of outright violence, Black Americans continue to face subvert and institutional racism.

Now 76 years old and retired, Henry keeps busy with his writing and human rights work. Sometime before 1996, he realized that he wouldn’t be able to change the world as much as he thought he might be able to back when he was 18 or 21. But he continues to savor the challenge.

The ills that Henry has dedicated his life to fighting persist today. But he has taken a lesson that he taught Denison’s class of 1996 for himself: “You’re never going to find the perfect solution or reach the ideal state – Martin Luther King’s ‘beloved community’ – but you will enrich yourself and others in trying.”

Jack Nimesheim writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation and donations from readers. Sign up for The Reporting Project newsletter here.