A writer looks for hope in her struggling homeland

Fayette County, Pennsylvania, homeowners pay for insurance against “mine subsidence.” That’s the real estate term for what happens when collapsing mine tunnels beneath a property change the level of the earth’s surface. As the ceilings of abandoned underground mining operations gradually cave in, homes built on the ground above the mines come apart. The walls seem to unzip, with jagged diagonal lines appearing where brick walls have split.

The post office in the Fayette County town of Isabella, Pennsylvania, shows clear signs of mine subsidence damage: at one corner, it’s crumbling. As the town population has dwindled, so have the hours of service. These days, the post office is only staffed for two hours a day–sometimes less, if the clerk feels like closing up early.

Isabella is a coal patch, an unincorporated company town built around the entrance to a mine. Founded in 1907, it once supported two beer gardens, a general store and an elementary school. A trolley line connected Isabella to Pittsburgh, fifty miles to the north, stopping at all the other coal patch and steel mill towns in between. But since the mine shut down in the mid 1980s, the foundations of the community have disintegrated.

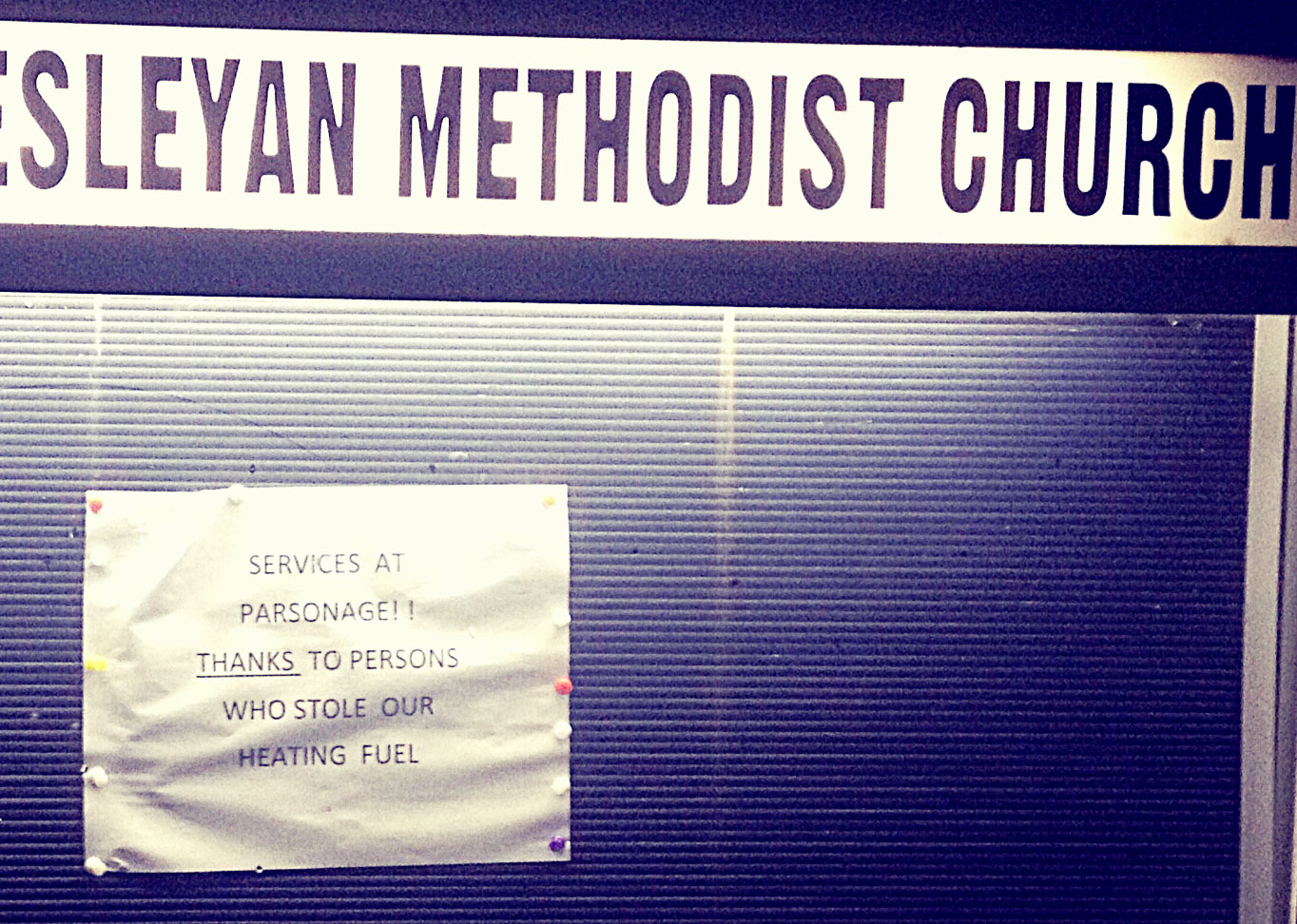

Today, the last trolley is long gone. The store’s windows are boarded up. The bars, the school, about 260 brick coke ovens, and almost all of the mine buildings have been demolished. The tiny Catholic church closed its doors in 2008. A tiny Methodist church struggles to hang on.

Like rural areas across the country, Fayette County is depopulating. A 2013 article said the population had declined 8.7% from 2000, and county figures from 2015 – the most recent – show a drop of another 2.2% since 2010. The 2010 census put the population of Isabella at 181.

Majestic oaks and maples tower over the winding country road leading into this Appalachian town, forming an arch of gold and red in the autumn. Down in the valley, sunlight flashes on the river. Signs giving information about Revolutionary War battles or the history of local industry dot the hillsides. Some front porches are decorated with handmade country crafts, though as the older generation passes away, these artistic expressions are becoming more rare.

In its heyday, the coal mine employed immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. My Italian great-uncles worked alongside miners from Poland and Russia. My grandfather was born in Isabella. As an adult, he worked for a few years in the mines until a back injury sent him into early retirement.

But today, Isabella has no real economy, and the other villages in the area are not doing much better. The county’s unemployment rate is 2.2% higher than the state average. Not only have the mines, with their large labor forces, closed down, but so have factories, schools, and public services. Though fracking has moved in to extract natural gas from the Marcellus Shale, the wear and tear on the environment and infrastructure has not been offset by a significant uptick in jobs.

These days, even inexpensive chain restaurants like the Golden Corral, a longtime local favorite with both seniors and families, are closing their doors. A Facebook page celebrating one Fayette County town is called “Things that aren’t there anymore! Brownsville, PA and surrounding areas.”

As churches, stores, community groups, and sources of income disappear, as resources become a little more scarce each year, an atmosphere of distrust takes root and grows.

To hear my relatives tell it, people have always been fighting with each other in Isabella. When I was a kid, and more people lived there, on a summer night you could hear roaring family feuds being carried out in the narrow streets. Maybe people figured the town was so small that everyone knew each other’s business, anyway, so why try to hide it? Or maybe the young- and middle-aged people with little to do and few employment prospects just had energy and nowhere to spend it.

People sell each other what they can – labor or household objects – for a little extra cash, but price gouging is rampant. Out of work forty-somethings are hired by the elderly for lawn mowing at a rate that’s about as steep as the sloping landscape. And then there’s the black market in pain pills.

Fayette County has one of the nation’s highest percentages of drug overdose deaths. A new prescription drug monitoring program requires prescribers to look patients up in a statewide database. Records get flagged as suspicious when someone fills multiple prescriptions within a short period of time. But the reasons for the multiple prescriptions aren’t necessarily taken into consideration by overworked providers who feel pressure to comply with the regulations.

As a result, many people who suffer from chronic pain are unable to access the medication they need to live functional lives. One resident told me that in order to manage severe pain related to blood clots in her leg, she buys oxycodone from her neighbor at $10 a pill. Meanwhile, people who do have prescriptions have an incentive to keep refilling them, even if they’re no longer taking the pills themselves.

Growing up, I always felt like I lived in a blue state, since the Democrats had reliably won every presidential election since 1992. But people who had lived there longer described it as more of a T shape, with big blue patches around Pittsburgh and Philadelphia and solid red across the central and northern parts of the state.

Trump’s message found many fans here. His embrace of fossil fuels, including coal, made him a hero to those who want to believe that coal will make a comeback. And his promise to bring jobs back to the U.S. kindled something almost like hope.

A lot of the people around Fayette County are registered Democrats, but they lean conservative. It’s a blue collar region with a history of organized labor, and those who once stood up to mine owners to secure better conditions now see themselves as standing up for the coal industry against a distant government that’s out of touch with regular people’s reality.

In a speech delivered in June 2016 to an invitation-only audience of about 250 in Monessen, a former steel town about half an hour downriver, Trump said, “Hillary Clinton wants to shut down energy production and shut down the mines, and she said it just recently, she wants to shut down the miners. I want to do exactly the opposite.”

Trump’s economic promises hit home, but perhaps even more importantly, the candidate’s attention was balm for the region’s hurting ego, which has been pummelled by the last three decades. Some voters were enthusiastic about his platform and some were reserving judgment, but lots of people here felt seen by Trump. He successfully made them feel like he was their candidate, and he would represent their interests against the corrupt political establishment. And he took 64% of the Fayette County vote.

Don Pavelko, the Democratic mayor of Donora, a small nearby town, said after the speech, “We finally have somebody who is showing some interest in the Mon Valley and I’m here to see what Mr. Trump will do for Donora and the Mon Valley. The valley has been an abandoned stepchild for years. It’s about time somebody showed they’re thinking of us.”

Pavelko’s poignant “abandoned stepchild” metaphor makes one wonder what would happen if, somehow, the vacant spaces left by the withdrawal of industry and the collapse of community institutions could be filled with something other than rhetoric. What will it take to restart the heart of this region? How can neighbors who have been taught to fear and compete with one another learn to trust in community again?

For now, Isabella, and the relationships between its dwindling number of residents, will continue crumbling. Forgotten towns like this one are shaping the nation’s future. How to rebuild these environmental, economic, and community foundations isn’t immediately clear, but doing so is essential, not only for the sake of the people living there, but for the health of the country.

Perhaps the place to begin is taking a sincere interest in a neighbor’s well-being. Mutual care and concern could end up being the best insurance of all.

Angela Galik is a writer and composer who grew up in rural Southwest PA. She lives on Colorado’s Front Range and works as Director of Communications at the Institute for the Psychology of Eating. Her writing has appeared in We’Moon and All Roads Will Lead You Home.