Paul Free’s favorite part about smuggling drugs across the Mexico-U.S. border in the 1970s wasn’t the adrenaline rush, the money or the clout. He took more pride in bearing witness to Southern California’s coastal sea life, the way the sun glistened on the Pacific Ocean and the number of fish he could catch while traveling.

Free’s father owned the quintessential 1960s grocery store in Coronado, California. From a young age, Free assumed the role of salesman, selling everything from soda to bread.

But he grew tired of the simplicity of it all and went from moving dozens of glass bottles of Coca-Cola for 10 cents a pop to moving pounds of cannabis for immense profit. His smuggling operation began in the early ’70s with frequent trips across the border, where he’d purchase cannabis for his own personal use.

“It was cheaper over there, and abundant, so I started smuggling it,” Free said.

Free enjoyed the lifestyle and felt a sense of gratification in being able to out-maneuver the authorities.

Until he couldn’t.

In 1975, Free was arrested on a marijuana possession charge with three pounds of product. Initially, his sentence yielded five years in a California state penitentiary but was reduced to three years thanks to his legal team.

Now an Ohio resident, Free, 73, embodies a stark contradiction, having endured a life mostly spent in prison for marijuana possession — a substance that now could be on the brink of legalization in this state. His story mirrors thousands of other Ohioans, overshadowed by the fact that the state stands poised to profit from the very activity that resulted in incarceration for many.

Ohio voters could elect next week to legalize recreational marijuana use, a move that highlights the discord between a potential financial boon and the ongoing imprisonment of individuals here for conduct already legal in 23 states, three U.S. territories and the District of Columbia.

Temptation after an injury

Free’s passion for sea life prompted him to enroll at San Diego State University after he was first released from prison in the late 1970s, seeking a bachelor’s degree in marine biology.

After graduating from SDSU, Free worked as a bartender, and then as the manager of the Coronado Playhouse, a dinner theater in San Diego.

In 1993, he suffered a shoulder injury that required expensive surgery and a long recovery time. An old contact of his, still involved in the smuggling scene, had a lucrative job for Free, one that could assuage his financial troubles.

The job was simple, Free thought: Drive a truck full of cannabis from southern California to Detroit, Michigan, in exchange for $3,000. He completed the job seamlessly, returned home for his surgery and resumed his life.

Nine months later, in June 1994, he was arrested by police and found that his associates had betrayed him in exchange for lighter sentences for themselves.

The prosecutors offered Free a lighter sentence, too, if he would provide information about other operations in the southern California region.

“At that time, I had been out of the business for a while and really had nothing to tell them,” Free said. “And if I did, I wouldn’t have told them anyway. It’s against my principles.”

Free’s perceived lack of cooperation landed him in a courtroom, accused of an array of offenses.

“They accused me of things that I had nothing to do with,” Free said, “Loads of product that came across the border in Texas and Arizona. They threw it all on me.”

Sitting in the courtroom, Free felt like he was watching someone else’s trial.

“People I’d never seen before in my life stood in front of the jury and said, ‘Oh yeah, Paul Free and I did this and that together.’”

Free was sentenced to life in prison without parole in 1995.

According to Dr. Doug Berman, Executive Director of the Drug Enforcement and Policy Center at Ohio State University, this period marked a turning point in U.S. public opinion on cannabis.

Sobering up from ‘the hangover’

Berman explained that drug-related offenders in late 1980s and early 1990s received the harshest sentences, and since then, the United States has had to grapple with the social fallout of locking up non-violent, occasionally first-time offenders for extensive periods of time.

“I’m inclined to call this period ‘the hangover,’” Berman added. “A lot of people were hearing stories of life sentences being imposed for only one offense, and I think the country really started considering if such harsh enforcement was good.”

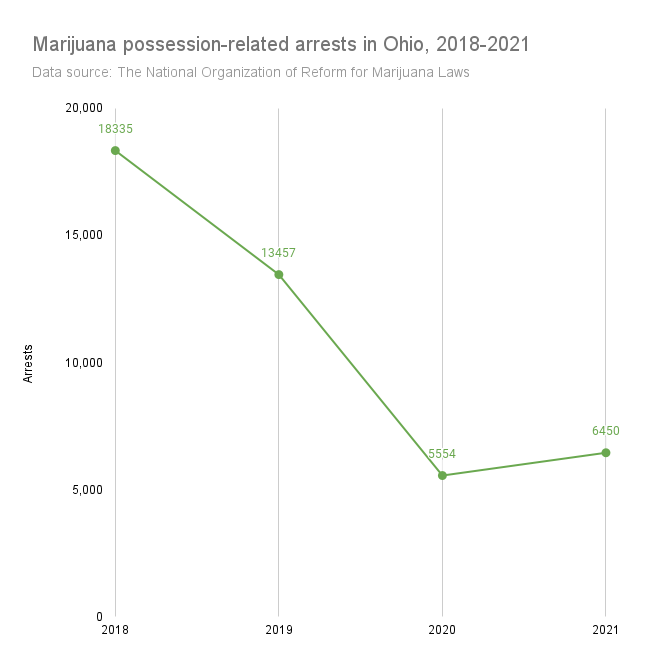

But that hasn’t stopped incarceration. Since 2018, two years after Ohio legalized cannabis medicinally, the National Organization of Reform for Marijuana Laws found that 43,796 people have been arrested in the state for marijuana possession alone, with an average of less than 50% of agencies reporting.

And while their sentences may not be for life, many have questioned the logic of continuing to incarcerate individuals for possessing something that is institutionally sanctioned and supported in some places.

On Nov. 7, Ohio residents will vote on whether to legalize recreational marijuana use for Ohioans over age 21. House Bill 168 — the foundation for Issue 2 — will permit Ohioans to cultivate, purchase and possess marijuana if the issue passes, and will impose a 10% sales tax on all sales of the substance.

That sales tax, Berman’s institute estimates, could bring in between $276 million and $403 million in tax revenue within the first five years of legalization.

Much of that money will go back into the community, according to the language on the ballot: 36% will go to the cannabis social equity and jobs fund; 36% will go to the host community cannabis facilities fund; 25% will go to the substance abuse and addiction fund and the remaining 3% will go to the division of cannabis control and tax commission fund.

Since the first sale of medical marijuana in January 2019, Ohio has generated $79.8 million in taxes, meaning that Berman’s projections estimate a 405% increase in revenue with recreational legalization.

That increase, Berman said, is a result of artificial inflation in the recreational market after decades of criminalization, stigmatization and limited supply created an environment primed for corporations to exploit historical prejudices for profit.

Given the profit Ohio likely stands to receive, various advocates for cannabis reform have pushed for a commitment from the state to reinvest a portion of the funds in social programs and support for those affected by cannabis’ criminalized past.

“There needs to be programs created to help those dealing with these charges,” said AmandaLynn Reese, chief program officer of Harm Reduction Ohio. “The state needs to help those affected reintegrate into society.”

Both Berman and Reese point to potential benefits of a system that utilizes a small portion of tax revenue to fund such programs.

“Not only would it help those harmed in the past, but it would set great precedence for the rest of the country,” Reese said.

The assistance that Reese hopes for can take time, resources, and patience to actualize. Even if approved, the mobilization of these projects may leave many caught in the middle.

Until these safety nets become a reality, Berman has advocated for reform from within the existing justice paths for expungement. Judges often commute sentences to prisoners with terminal illness, family emergencies, and other extenuating circumstances. Berman believes the same grace should be extended to those with first-time, nonviolent cannabis possession-related charges tethered to their record.

Other states have employed programs similar to those Berman and Reese propose. In 2021, New York stipulated that 40% of the tax revenue from marijuana sales will go to a community reinvestment fund. The fund aims to support communities that were disproportionately impacted by cannabis arrests.

When Illinois legalized recreational cannabis in 2019, the law included provisions for the expungement of nearly 500,000 marijuana-related arrest records, and Gov. J.B. Pritzker pardoned more than 11,000 low-level marijuana convictions in conjunction with the law.

Free gains freedom

While states across the country began efforts to legalize cannabis, Free sat in prison, remaining incarcerated in Arizona nine years after the state legalized medical marijuana. From his one-man, cinder block prison cell, Free watched the horrors of the 9/11 attacks in 2001, witnessed the election of the United State’s first African American president, and skirted the 2008 housing crisis.

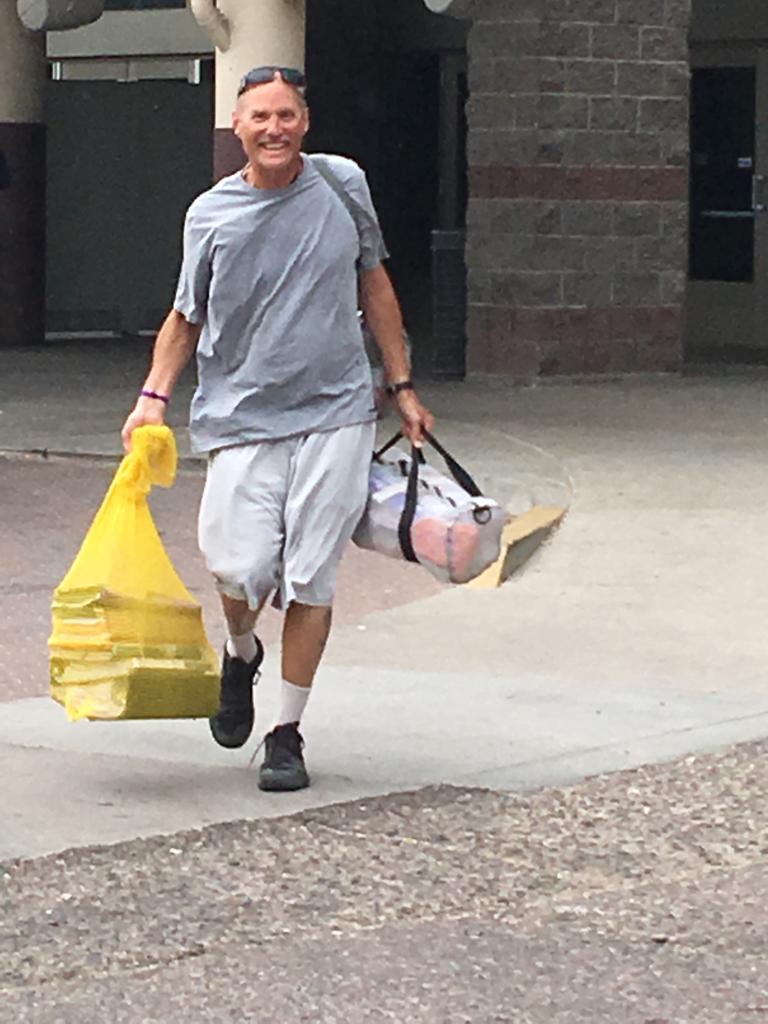

In 2016, after two prior attempts with three U.S. presidents, Free was granted clemency by President Barack Obama. Three years later, Free was officially a free man.

Two of the first purchases made by Free upon his release was an old laptop and printer, which he used to make flyers calling for the federal legalization of cannabis. He strapped them to his body, set his eyes on every congressional office on Capitol Hill, and stepped off the D.C. metro escalator and onto the National Mall for the first time in his life.

“I’ll never forget when I looked up and saw the Washington Monument and turned around the other way and saw the Capitol building for the first time,” Free said. “I had tears in my eyes.”

What’s Next?

If cannabis is legalized, Ohio likely will find itself at a crossroads. One path would be a commitment to restorative justice, and the other, as Berman notes, would solidify a boot-strap mentality. The first path would be an acknowledgement of the so-called hangover, which Berman asserts we are in the midst of recovering from, and the other, Berman says, would be a failure to address the shift in public opinion on drug enforcement.

“It’s the fundamental damage it did to individuals caught up in the drug war,” Berman said. “It’s collateral damage. I think a lot of people recognize that this was a failed approach.”

The perceived change in public opinion has left some Ohio politicians unsure about how to discuss the upcoming vote. Journalists from TheReportingProject.org contacted state representatives Jamie Callender, R-Concord, and Ron Ferguson, R-Wintersville, for comment in early October, and they did not respond.

The Baldwin Wallace Community Research Institute surveyed Ohioans on their opinions on the legalization of recreational cannabis use. Almost 60% of the 850 registered voters who responded said they plan to vote yes on Issue 2.

The majority support for Issue 2 outlined in the polling parallels Berman’s observation of cultural shift and the need for congressional acknowledgement of that shift.

Berman presents similarities between the public’s opinion on alcohol and cannabis. For decades, America has been battling the illegal practice of drinking and driving. The same can be said for the intake of cannabis. The country had an issue with its substance use, and introduced cultural movements for change.

“Sometimes, we unduly rely on law, especially criminal law, to do what we need to achieve through culture,” Berman said.

That cultural change around how Americans ponder cannabis use is what Free and thousands of other advocates alike are working hard to inspire.

Free now spends his days in Zanesville, Ohio, with his girlfriend and fellow cannabis-reform advocate, Beth Curtis. And while many things have changed during the course of his life, his passion for wildlife has not. Though there’s no local sea life, Free still loves the wildlife, and enjoys watching deer and fawns frolic beneath the red, yellow and orange autumn leaves from his second-story bedroom window.

Eitan Silver, Jack Wolf and Caliyah Bennett write for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s journalism program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation. thereportingproject@denison.edu