The man in the white cowboy hat knew the jig was up the day he entered a Chicago courtroom, placed his hand on the Bible and swore to tell the whole truth.

Richard Hart wasn’t on trial that day in September 1951. The prosecution had called him to the stand as a witness in his brother’s tax evasion hearing. But the longtime prohibition agent and larger-than-life Nebraska lawman faced something arguably harder than hard time.

He knew the identity he had carefully crafted for himself over decades, brick by brick – the self he had created with much deceit and many good deeds – was about to be blown to smithereens by the lawyer standing before him wearing a three-piece suit.

He knew he was about to be revealed.

Hart, now 59-years-old, portly and wearing a necktie too short to reach his belly button, slowly walked to the witness stand before a packed courtroom on a cool, calm morning in the Windy City. He took his seat, turned to the judge and, in a nervous, shaky voice, asked a favor.

“May I keep my cowboy hat on?”

The prosecutor stood up then and fired a simple question.

“What’s your name?”

“Richard J. Hart,” the witness answered.

“No, no,” the prosecutor said, shaking his head. “What’s your real name? Your family name? The name on your birth certificate?”

I imagine Hart paused on the witness stand and briefly considered an extraordinary life. The day he fled his poor Italian upbringing in Brooklyn and caught a westbound train at age 15. The way he taught himself to shoot and ride and do the things his heroes did in the westerns. The accessories he added in Oklahoma to look the part: riding breeches, a billowing shirt, a bandanna tied ‘round his neck, two pearl-handled pistols, and a nickname he hung on himself. Two Gun. Richard “Two Gun” Hart.

Then his move to Nebraska and marriage and children and a horse he named Buckskin Betty and a career of catching bootleggers, bank robbers and stone-cold killers, and then reading his name in the newspapers.

I imagine he thought about all this, and then, right before he answered, took off his 10-gallon hat and lowered it to his heart, like the movie cowboys did when they wanted to act heartfelt.

“What’s your real name?”

“Vincenzo,” he answered. “V-I-N-C-E-N-Z-O.”

“My name’s Vincenzo Capone.”

The man long known as Richard “Two Gun” Hart, wounded World War I hero, then a Nebraska-famous lawman who busted bad guys and served as the right hand of justice, was in fact the eldest brother of Al Capone, the country’s most notorious mob boss.

He had conveniently hidden this fact from his Prohibition-era bosses, his police superiors, and the people of Homer, Nebraska, where he had lived off-and-on for decades and served as town marshal and post commander of the local American Legion.

He had hidden it from Kathleen, his wife of 30 years, and his kids, too.

That day, the headlines blared the truth from Chicago to Omaha to Denver, scattering the news across the Great Plains to the sons and daughters and grandkids of pioneers and homesteaders and gold rushers – to people who knew a little something about the art of American reinvention.

People were shocked, same as we are today. They were also fascinated, same as we are today.

“On the one hand, we lionize the Capone family. On the other hand, we love the notion of the cowboy gunslinger lawman,” says Aaron Duncan, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln professor who has studied the mythology of the American West. “If you can fit both into the same story – well, it’s its own movie, isn’t it?”

* * *

You could disappear. Hell, the government was begging you to disappear.

It’s hard to fathom now, in a modern age defined by connectedness, but a century-and-a-half ago, millions of Americans said goodbye to their relatives, hitched up their wagons and bumped west 1,000 or 2,000 miles, never to be seen again.

Over time, this experience has been flattened in our minds, reduced to cliché, explained in sentence fragments. Free land! The promise of riches! Adventure!

A chance to begin again.

“The West, broadly defined, is the region, across time, that Americans have looked to as a place to go and start the world over again,” says Heather Fryer, a historian and director of Creighton University’s American studies department.

This mass migration bred a powerful pioneer mythology, one that dovetailed nicely with the way Americans already viewed themselves and their young country. They celebrated the mythology in dime-store novels and later on the silver screen: Billy the Kid, whose real name was Henry; Doc Middleton, whose real name was James; Wyatt Earp whose real name was…well, Wyatt Earp.

Sure, you might take an arrow through the heart and donate your scalp to a justifiably pissed-off Cherokee. Yes, you might die of starvation or hypothermia or dysentery or mumps or you might place a shotgun to your head and pull the trigger after the endless whistling wind activated dark voices inside your brain.

But if you survived, you owned a plow and a little piece of treeless land and the right to make as much or as little of your life as you and your God pleased. You literally reaped what you sowed.

“Like most everything, there is some truth to it,” Duncan said. “But like a lot of American mythology, what we’re actually talking about is a middle-to-upper class, white, heterosexual male dream.”

Dig into the mythology, burrow past the clichés, and what you find, historians say, are the stories of countless people who, for countless reasons, wanted, or in many cases needed, to reinvent themselves.

A stack of unpaid bills in Boston. A warrant for your arrest in Philadelphia. A jerk for a boss. A drunk for a dad. A mother who couldn’t possibly feed you and all your younger siblings. A famine in Ireland.

Men moved to Iowa and became women, notes Fryer, pointing to research by author and Washington State University professor Peter Boag. Women moved to Oklahoma and became men. Light-skinned African Americans disappeared from Mississippi sharecropping plantations and reappeared in Wyoming, newly white.

Fryer’s own great grandmother showed up solo in Oregon, a popular cook at a logging camp. She had kids and grandkids back in Nebraska, had lived nearly an entire life as the immigrant matriarch of a family.

Only after her death did her offspring realize that great-grandma had started and then abandoned her first family, leaving a bad marriage, and disappeared to start all over again in the northwest.

“I think, on some level, every family out here has a story like that, whether they know it or not,” Fryer says. “The truth is that nobody was looking for her.”

Well-fed, well-off people, content with the social constructs of daily life, do not load up a wagonfull of belongings and rumble 2,000 miles so they can take up residence in a sod house that they dig out of a prairie hillside with their own two hands.

Desperate people do.

Richard “Two Gun” Hart showed up in Nebraska a half-century after the pioneers, after the telegraph lines and the railroads had “settled” the place. When he did, he adopted the uniform and persona of an already bygone era – a persona that seems equal parts cinematic and nostalgic.

We will never know why he did this. The man born as Vincenzo Capone seems to have taken his motivation to his grave. When he left New York as a 15-year-old, maybe he had wearied of the rules and responsibilities of being the eldest son in a poor, 11-person Italian-American family, as Fryer suspects. Or, as his biographer, screenwriter Jeff McArthur guesses, maybe Vincenzo had gotten crosswise with his strict father or with the law.

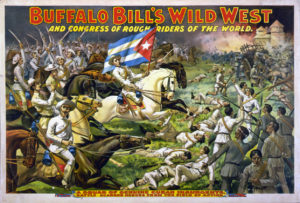

Or maybe the New York City boy just wanted to run away and join the circus. Soon after he reached Oklahoma, the teenager, now calling himself by the last name Hart, found work with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch, a traveling Wild West show that starred an aging Buffalo Bill Cody and featured staged cowboy-and-Indian shootouts.

We have to guess about his motivation, but we don’t about his timing. As he played, and then became, a cowboy lawman, many of the wanderers who used to stop in places like Nebraska were busy pushing further west, to California and Oregon and the shores of the Pacific.

In later decades, they left for Alaska and for Hawaii. Today, Fryer says, many of the residents of your average no-name Hawaiian fishing village are mainland transplants who tend not to say too much about how or why they arrived. She would know, as she is currently living in one while researching her next book. She talked to me on her cell phone while dodging some unruly chickens and a pack of hungry dogs wandering through the town square. Even this small town in Hawaii, maybe one of the most disconnected places in all of America, is still connected, she points out.

Once the frontier doesn’t feel like the frontier anymore – once the west, however we define it, has rules – then a certain number of people will try to find the next frontier.

Which begs the question: What happens when there’s no frontier left?

* * *

The burly ex-Navy SEAL knew the jig was up the day a reporter called him on his cell.

For years, Trey Smith had built a name for himself as an attractive-as-hell online persona in a corner of Twitter hopelessly devoted to Nebraska Cornhuskers football.

He offered his thoughts on Coach Bo Pelini, on the shoddy quarterback play, on bad tackling. But his sphere of influence quickly expanded beyond football.

Soon he was offering thoughts on the American military, thoughts that his Twitter followers took oh-so-seriously since Trey was a retired Navy SEAL and SEAL instructor who had once taught Chris Kyle – the famed SEAL celebrated in Clint Eastwood’s “American Sniper”.

He good naturedly took crap for his love of peanut butter-and-onion sandwiches and also mercilessly savaged Husker sportswriters whom he believed knew nothing about football.

A lot of people started to think Trey was pretty funny. A lot of people found themselves magnetically pulled toward this ex-Navy SEAL who loved flannel shirts, the red-white-and-blue and a cold beer on the back deck at sunset.

Trey’s relationships with these people deepened, spread from Twitter into real life. He gave advice to a nurse named Nikki who was struggling to raise her teenage son. Over beers, he counseled an Iraq War veteran named Stuart suffering from post-traumatic stress after his latest deployment.

He kept Dell Richmond, an insurance claims handler, company online for hours after his wife got sick. Then he came to the funeral in his flannel shirt and gave Richmond a hug.

“He showed up. I appreciated that so much,” Richmond says. “Trey was the sort of guy who could be rough on the exterior, but when you got to him, you knew he had a good heart.”

Then Trey himself got sick. Throat cancer, he confided in direct messages to his Twitter pals. He would beat it.

But he didn’t. Trey’s daughter came onto his account one day and told his followers that he had passed.

They were burying him near his cabin in the Wyoming mountains. There would be no Nebraska service. Go have a beer together and remember my dad, she told Stuart.

And so they did. They met at Lincoln’s Zipline Brewery and toasted Trey with story after story, and beer after beer. They raised thousands of dollars for a cancer charity. They cried.

The cracks finally began to show a couple months later, when a new Twitter account manned by someone named Ken began to follow and befriend Trey’s old fan group. He said he was old friends with Trey. But he sounded like Trey, so much that people got suspicious.

Stuart eventually dug up a photo of Ken and realized: Trey looked exactly like Ken, because Trey was Ken.

Trey Smith had never died. He had never died because he had never lived.

Trey’s real name is Ken Peterson, and he’s not an ex-SEAL who trained Chris Kyle. He’s a run-of-the-mill salesman who lives near Lincoln.

When I called and identified myself as a columnist for the Omaha World-Herald, Ken knew he was about to be revealed.

I asked him why he had invented the persona of Trey Smith, why he had tricked thousands of people, including some who grew very close to him, into believing his tall tale of being a military hero.

He spun me an impossible-to-believe story about a social media experiment conducted by a devious behavioral psychologist whom Ken wouldn’t name, and an academic research project whose principal researchers – including Ken himself – met at a gas station on the outskirts of Greenwood, Nebraska.

He wouldn’t give me the names of any of the other five researchers, either.

I told Ken Peterson I didn’t believe him.

“Am I proud of what I did? Hell no, and I understand why people are salty now,” Ken told me. “I get it. I appreciate it. And if I could take it back, I never would have gone to Twitter.com. Swear to God.”

I’m not sure that Ken should swear to a higher power anymore than Vincenzo should place his hand on the Bible and swear to tell the whole truth.

Social media is the new Wild West, the experts say, a place where the rules are being written even as we tweet and Instagram our opinions, meals, lives.

An estimated 15-percent of all social media accounts are fraudulent in some way, according to a groundbreaking paper from Indiana University infomatics and computer science researchers.

Many of those are bots, out to convince us that they are real to open our pocketbooks and sway our opinions – even to influence the outcome of presidential elections.

But an unknown number of these fake accounts are simply real people choosing to create a new identity online. In a survey of the virtual world “Second Life,” nearly four of every 10 real people surveyed admitted to creating multiple accounts, usually being “themselves” on one account and then trying on a new persona with another.

Want to be a high-powered Wall Street businessman when, in fact, you are a tax accountant from Sandusky, Ohio? Have a yearning to be a sexy single co-ed on Instagram when you are a middle-aged man with a family, a mortgage and a paunch?

Want to tell people that you are a Navy SEAL who trained Chris Kyle, so earnest and heroic that they confide their very real problems to you and then mourn you when you die?

That’s nearly impossible to get away with in real life. It isn’t online.

Almost all of us present some idealized versions of ourselves on social media, say those who study it.

Some of us, like Ken Peterson, take it to the extreme and re-invent themselves almost entirely.

“Isn’t it interesting that he did want to help people, but he felt he couldn’t do so from an honest perspective?” asks Duncan, who has written extensively on the idea of the American self-made man. “It’s like he felt that without the lies, he couldn’t credibly offer the truth.”

When the people who considered themselves close friends of Trey Smith discovered the truth, they erupted in anger. They flamed Trey/Ken online. They told me if they saw him in public, they would challenge him to a fistfight, or simply stare right through him as if he didn’t exist.

In their fury, few stopped to reflect on a question nagging me: Wasn’t Trey Smith’s story always a little too good to be true?

Didn’t his tale, like the story Two Gun Hart had told a previous generation of Nebraskans, require both a colorful storyteller and a group of people gathered around the proverbial campfire, listening intently?

* * *

Not long ago I was lingering near the wall at my small-town high school alumni banquet’s cocktail hour when a tiny, white-haired woman from the Class of 1951 walked up to introduce herself.

“We’re related,” she said. “I’m your Grandpa Richard’s cousin.”

I peered down at her nametag. The name she had scrawled in pen was Ardyce Rose Hanson.

My last name is Hansen.

“If we’re related,” I asked, “why are our last names spelled two different ways?”

“Why, let me tell you,” the tiny old woman named Ardyce Rose Hanson said.

The trouble, she said, started with her great-uncle Pete, who stole several horses from the family of famed author Willa Cather who, like Ardyce Rose and I, had graduated from Red Cloud High School.

The authorities were on the scent. Pete the Horse Thief fled to Denver, which evidently was far away enough to elude the long arm of the small-town Nebraska law in the late 19th century.

But Pete’s family, his parents and siblings, still lived in Red Cloud, and they were ashamed.

In their shame, they changed their name from Hansen – the correct Danish spelling – to Hanson.

Then, a generation later, my branch of the family changed it back to the “e”. Hers never did.

“You mean to tell me,” I said, “that our family changed its name because a 19th century horse-thieving Hansen stole from the family of the woman who wrote ‘My Antonia’ and ‘O’ Pioneers!?”

Ardyce Rose Hanson all but shrugged. “Yup,” she said, and wandered away to find her old classmates.

I have told and re-told my family’s story of horse thievery and assumed identity many times. I wrote a column about it in The Omaha World-Herald.

But the story has always nagged at me because there’s a gap in it big enough to drive a whole team of stolen horses through.

Simply put: What good did it do my family to change a single vowel? Everyone in Red Cloud would have known that the Hansens had become Hansons because of crooked Uncle Pete. If anything, the name change would seem to heighten the ridicule, not hide the shame.

I wonder if the story Ardyce Rose Hanson told me is true.

I wonder if we simply want it to be true.

Richard “Two Gun” Hart walked around small-town Nebraska in the mid-20th century looking very much like a Brooklyn teenager’s slightly ridiculous dream of what a Nebraska lawman should look like.

Hart wore a big white hat, a billowing shirt, cowboy boots and two pearl-handled pistols.

Back then, men in small-town Nebraska wore bowler hats and dress shoes. The only people dressed like Two Gun Hart were movie star cowboys.

The residents of Homer, Nebraska had to notice this. They had to wonder when he claimed to be half-Indian to explain his olive complexion. Kathleen had to wonder when not a single Hart relative showed at their wedding.

Trey Smith told people that not only was he a Navy SEAL, but a SEAL instructor. He wasn’t only a SEAL instructor, but a man who had taught the most famous Navy SEAL in history everything he knew.

His Twitter friends had to notice. They had to wonder when he said he couldn’t give them his real first name – just his nickname – because he was under constant threat. They had to wonder why the Navy or his hometown paper or anyone else failed to celebrate him, to eulogize him, when he died suddenly of a mysterious cancer.

Yes, Two Gun and Trey built the façade of a new identity. But it stood for as long as it did only because the people didn’t tap on it and test its strength.

“The façade doesn’t work unless people are willing to believe it,” Fryer says. “And there are often a lot of willing believers.”

The unsettling truth is that America itself is built as much on the things we don’t talk about as the things we do, Fryer says. The unsettling truth is that none of us exist like we see ourselves unless we buy into a few lies.

“Think about all the things we don’t talk about in society, inside our own families. The negative space in this whole history of reinvention is built from the things we have, things we acquire.

“America is built upon that silence. It’s built on the silence of those of us who are the audience in the story, too.”

* * *

Not long ago, Harry Hart, the lone living son of Richard “Two Gun” Hart, wheeled himself out of his room at a Lincoln nursing home and into the sun-drenched porch where I waited.

We shook hands, and I tried to conceal my excitement at meeting the direct descendant of the long-hidden Capone.

But Harry Hart wasn’t able to give me what I wanted that day. Or maybe he wasn’t willing. Or maybe both.

Instead, Harry told me he didn’t remember the day his dad told him the truth. He said he didn’t much think about his dad’s real identity, or the identity he created, or why.

Harry talked for a long time about how his father Richard Hart taught him to hunt and fish. How he led Harry’s Boy Scout troop. How his old man loved to play the mandolin down at the Homer bar on Saturday nights, just because.

But his jaw tightened whenever I brought up the Hart-Capone switch. He grew testy, wordless.

But I kept circling back to the day when the town of Homer, Nebraska, learned the truth about Two Gun, and finally, a brief breakthrough.

Harry Hart said then that Two Gun’s friends and loved ones took in the seemingly shocking news and reacted the way they reacted to a far-off thunderstorm.

They stared off at the horizon for just a second or two. They briefly considered the distant thunder and the roiling clouds and the flashes of light. Then they shrugged and went back to work.

Except, in reality, Harry Hart didn’t veer this far into imagery, didn’t struggle for metaphor. In plainer terms, he told me that no one much cared, and if they did, they didn’t care for long.

“To tell you the truth,” Harry Hart told me, “it didn’t mean piddly damn to me.”

Matthew Hansen is the managing editor at the Buffett Early Childhood Institute and a former columnist for the Omaha World-Herald. He was named 2015 Great Plains Journalist of the Year.