On a night when Carol Apacki had trouble sleeping, she found herself at the computer typing a search for “Rosie the Rocketer.”

That was the name her dad had given his airplane during World War II, and she knew he had done some amazing things with it during the war.

The first thing that came up in her search was a very long, technical discussion about whether her father, Maj. Charles Carpenter, actually could have strapped six bazookas onto the wings of his 800-pound reconnaissance plane made of cloth over a frame of welded steel and wood – and used those weapons to take out German tanks.

With what little evidence they had, and their knowledge of the Piper L-4 Grasshopper’s construction and capabilities, the war enthusiasts were casting doubt about whether the stories of his heroics were true. They suggested it was myth at best, and perhaps even wartime propaganda.

“As for ‘rosie,’ I’m inclined to dismiss it using a highly technical term: ‘Complete Bollocks,’” wrote one skeptic. “During WWII, propaganda, both against the enemy and to bolster the Home Front, was in high gear. Rosie appears to be the result of yet more ‘home-grown hero’ wishes.”

The typically mild-mannered and kindly Apacki could feel her face flush.

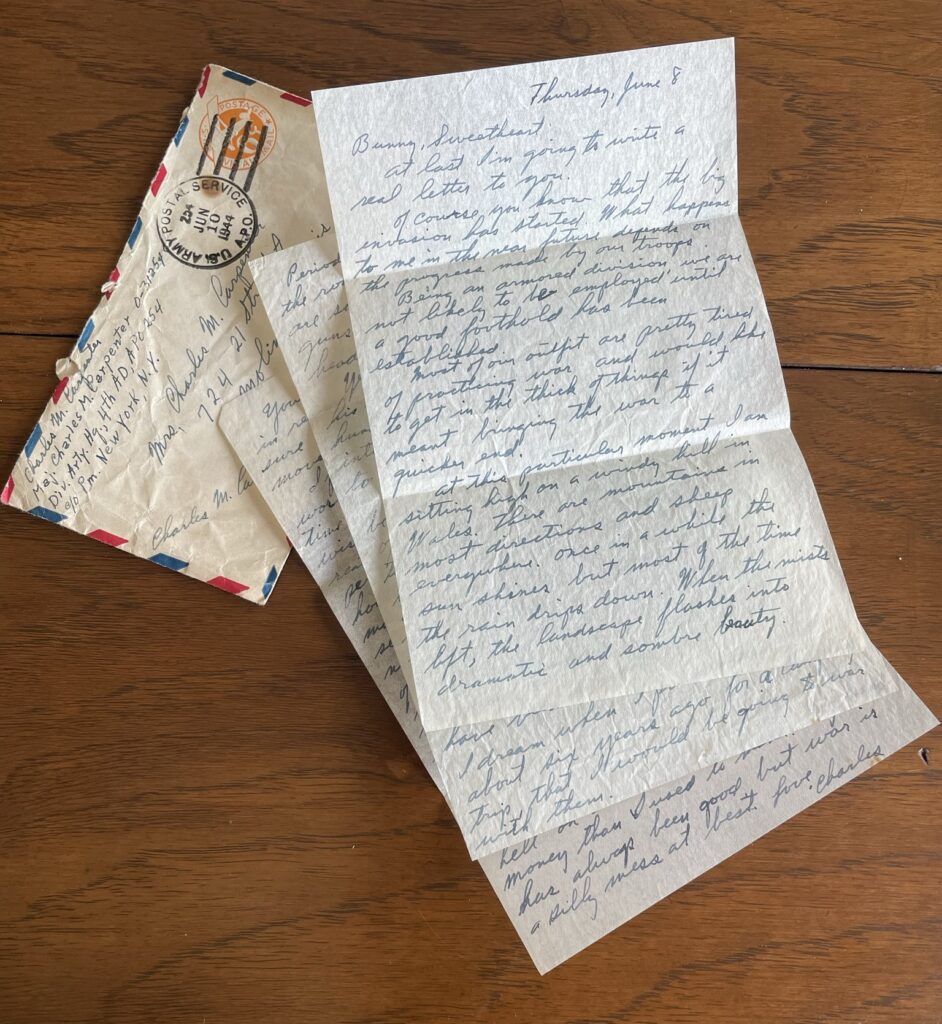

“That made me a little angry,” said Apacki, 81, of Granville, who had plenty of evidence that all of it is true. Her dad, a history teacher before and after the war, was a prolific letter writer, and her mom, Elda, had saved all of his letters and the photos he sent home.

So she pulled out box after box of letters, photos and documents and began to school the historians on the true story of a humble soldier and an otherwise quiet family man from Illinois who became known as “Bazooka Charlie.”

She was able to share, with evidence in his own handwriting, that Maj. Carpenter repeatedly flew his military version of a Piper Cub low over enemy troops – who were firing at him with pistols and rifles – and took out German tanks and other armored vehicles by firing missiles at them.

“There’s no question he saved countless lives,” Apacki said.

The doubters were stunned, and the online conversation caught the eye of Colin Powers, of La Pine, Oregon, a retired mechanical engineer and pilot who had restored several planes like the one Apacki’s dad flew.

Powers encouraged Apacki to write a story about her dad and offer it to the Experimental Aircraft Association Warbirds magazine.

It was a small act inspired by respect for her father and her passion for accuracy. It also led to a book and, almost miraculously, the recovery and restoration of the very plane Bazooka Charlie Carpenter flew on his remarkable missions. The plane is now in the Collings Foundation’s American Heritage Museum in Hudson, Massachusetts.

“In 2016, I got a call from a woman named Carol from Ohio,” said James P. Busha, the EAA magazine’s editor and a retired Oshkosh, Wisconsin, police detective lieutenant. “She said she wanted to submit a story about her dad. She said he was a pilot in World War II.

“Then she said her father was Charles Carpenter, and she must have thought the phone went dead. I was speechless,” Busha said. “This was a woman talking about her father, but it was a path into history.”

After the article appeared, it led to the discovery of her dad’s plane, and Busha contacted Apacki and said, ‘I think there’s a book here.’”

During his visit to Granville in 2020 to meet with Apacki and her husband, Ken, Busha said, “I was gobsmacked when I saw all of the letters and documents and diaries.” Apacki’s mother had collected and saved all of it.

Apacki was excited that someone wanted to help her tell her father’s story, to set the record straight and document the accomplishments of her father. She was thinking it would be a self-published book with enough copies to share with family and friends.

“I came back the next day, and she had these lemon cookies for me,” Busha said. “She told me, ‘I thought at first you might be a shyster, but you’re OK.’”

Busha and Apacki went on an amazing journey through time, and deep into history – including some personal history about the toll the war took on her father personally, on his marriage and on his family.

Apacki insisted that any book about her dad’s heroics should also include the effects on his mental and physical health – and the home-front heroics of her mother, who stood by him and held their family together during very difficult circumstances.

The story was not just about her dad, “but about what can happen to a marriage and a family. It’s many people’s story,” said Apacki, who was born while her father was at war. “I didn’t see my dad until I was 4 – and I didn’t really like him because he was so stern. I’m sure he had (post-traumatic stress disorder).”

Some veterans who have read the book or heard Apacki talk about the war’s effects on her dad and her family have been overwhelmed with appreciation for her willingness to be so open.

“I had people come up to me in tears – Vietnam veterans – who said, ‘Thank you for telling this story.’”

Apacki said the book started as a gift for her family. “I have 13 grandchildren who knew nothing of him. For my family, it has been a wonderful reconnection with their roots.”

Her dad grew up as one of six children in a home where his dad drank and gambled so much that he lost the family farm. Adversity led Carpenter as a 17-year-old to write this personal creed:

“I have resolved to exert all of my efforts toward being a nobler and stronger fellow, a gentleman, a scholar, a friend, and a real man. To the best of my ability, I will ever strive to self-control, self-improvement, freedom, wisdom, courage, generosity, truth and true nobility before gods and men. I will be better.” – Charles Marston Carpenter, 1929

Apacki said the creed framed who her father would become, but the war certainly challenged his values. He enlisted after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, and by 1944, he was firing missiles at German tanks as U.S. troops swept across Europe.

“He was seeing devastation,” she said. “He was brave, but not the man he wanted to be. He was a man of peace, and he saw untold deaths and destruction – day after day, endless death and destruction.”

In one incredible act of bravery, Carpenter, who had flown over an occupied village, landed near some U.S. troops just outside town and asked why the troops were not moving to rout the few Germans holding it.

The troops were under the impression the town was swarming with German troops, so they stayed at bay – until Carpenter jumped onto a U.S. tank, grabbed a 50-caliber machine gun and threatened to use it if they didn’t take the village.

His bold move inspired the troops, and they captured the village.

He might have been court-martialed for that move, if not for Maj. Gen. John Wood, Commander of the 4th Armored Division, who appreciated Carpenter’s moxie and his military skills, particularly his flying. Wood made Carpenter his personal reconnaissance pilot.

Apacki said she was stunned when she finally saw the plane she had read so much about.

“I couldn’t believe how small it was,” she said. “It looked like a kid’s toy.”

Her dad’s letters talked about being shot at by German troops, “and the restorer found bullet holes in the plane.”

The Collings Foundation located the plane in a museum in Austria, where it had been used after WWII to pull gliders into the air. The museum operators clearly didn’t know its history and sold it for a song, Busha said.

The foundation hired Colin Powers to restore the plane, given his experience rebuilding several Piper L-4’s.

“I restored it for Collings, but also for Carol,” Powers said.

When he stripped off the old fabric, he found that “Rosie had bullet holes, and a lot of signatures of the people who built it were on the wooden spars.”

It took him a year to restore it, and when it came time to apply the “Rosie the Rocketer” image on the new fabric skin, he invited Apacki’s daughter and Carpenter’s granddaughter, to put paintbrush to canvas.

Erin Pata is a graphic artist living in California, and Powers said she nailed the “nose art” on the plane.

As he was completing the restoration, Powers made a special request of Apacki.

“When I finished the restoration, I asked Carol for a photo of her mom to use as a pin-up in the cockpit,” he said. “Carol sent me a picture of her mom and Carol as a young child. It was a very special touch.”

At the Experimental Aircraft Association’s annual airshow in Oshkosh in July, an event that drew more than 800,000 enthusiasts over seven days, Apacki was a guest of honor and center of attention. She was invited to center stage to talk about her dad and the book, “Bazooka Charlie: The Unbelievable Story of Major Charles Carpenter and Rosie the Rocketer.”

She was beaming, Busha said, and taken aback by the several hundred people who came to hear her.

“I saw the youngest 80-year-old woman I have ever seen in my life,” he said. “You would have thought I was escorting an 18-year-old girl around. She was giddy. She was the star of the show. I introduced her as Charles Carpenter’s daughter, and she was the rock star.”

At the largest aviation event in the world, Busha said, everyone knows the name Charles Carpenter, “or the legend of him.”

And now they have a book full of facts about the man, the myth, the legend – the humble World War II hero Carol Apacki knew simply as dad.

Alan Miller writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of Denison University’s Journalism program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation and donations from readers. Sign up for The Reporting Project newsletter here.