“My children are the seventh generation of our family to reside in [our] home. The home two doors down from us was a part of the Underground Railroad.”

Allison Riggs testified to her deep heritage in the village of Alexandria during a hearing held by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency on June 8 at the Church of Christ in Alexandria. A standing-room-only crowd had gathered to voice concerns about an asphalt plant proposed for 1400 Tharp Road, the subject of the hearing, and another plant proposed for the northwest side, on the other side of the village.

Riggs testified against the air permit for the plant proposed by Scioto Materials, a division of The Shelly Company.

“We did not move to Alexandria for asphalt plants, but to escape them,” Riggs said.

Max Moore, a public involvement coordinator for the Ohio EPA, began the meeting, and then laid out what falls under the EPA’s jurisdiction. This includes the potential for groundwater contamination and air emissions that could violate the Clean Air Act. The EPA does not have jurisdiction over such things as traffic, air pollution generated from traffic, wildlife or zoning. The EPA writes and issues permits for facilities to regulate the output that can affect the air, water, and ground.

The second part of the evening was an open question-and-answer period. Moore attempted to focus questions from the nearly 200 concerned residents in attendance on the issues under the EPA’s jurisdiction.

The third and final part of the program was a public hearing about the application for an air permit by Scioto Materials. This is the next step in a process that could allow the company to build an asphalt plant at 1400 Tharp Road.

During the question and answer period, Christopher Hawkins, who lives between Alexandria and Granville, asked if it was possible to obtain the studies done about possible water contamination in Raccoon Creek. Max Moore explained that studies are public records that can be found on the EPA’s website and by making a public record request.

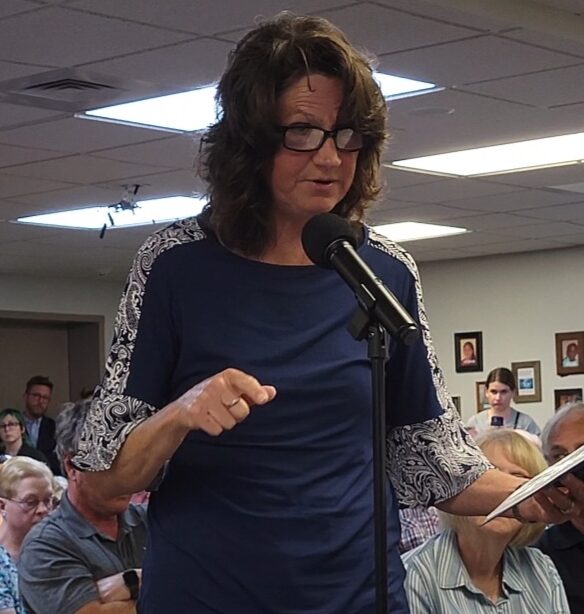

Christina Wieg, attorney with Frost Brown Todd Attorneys in Columbus, appeared as counsel representing Denison University and the Village of Granville. Before working at Frost Brown Todd, Wieg was employed by the Ohio EPA in the Division of Air Pollution Control.

The law firm submitted a records request on April 27, 2023, for documents related to the proposed asphalt plant, including supporting the air permit application. The air permit application was made available to the firm on May 26, 2023, a month later, but other documents were not made available.

“Air permits are complex,” Wieg said. “Providing meaningful technical comments in response to the draft permit is difficult, if not impossible, without reviewing the supporting application.”

Wieg requested that the remaining documents be provided, and that the period to make comments to the EPA should be extended, because counsel had only 14 days to digest the application, and some requested public records are still outstanding. (The public can submit written comments on the Scioto permit request to Benjamin.halton@epa.ohio.gov through Thursday, June 15.

Anthony Chenault, Ohio EPA public information officer, said that the office will respond to Wieg with any responsive records “within a reasonable period of time.”

“We anticipate the processing to be concluded shortly,” Chenault said.

All past violations of a company in Ohio are public records, but the Ohio EPA does not review a company’s past violations before issuing an air permit, according to Ben Halton, division of air pollution control. Halton said the EPA has the ability to tell companies they can no longer operate. Someone in the crowd shouted out: “How often has that happened?”

“I can’t say it never happens to anything,” Halton said.

Halton used this analogy for when the EPA issues permits: “It’s like getting a driver’s license,” saying that if someone passes a written test, and then a driver’s test, they get a license. The same is true with issuing an air permit.

Alexandria area resident Tracey Barnes said, “I understand that. But if I have four OVIs, I lose my license. … So why would a convicted violator of EPA regulations, your regulations, even be considered to build such an asphalt plant in an environment that is extremely vulnerable?”

Barnes and others asked that the Ohio EPA look at these plants as one entity, because two plants in Alexandria would cause concentrated air pollution.

The Scioto plant is proposed for land along Raccoon Creek and Rt. 37 on the southeast side of the village of 500 residents. Mar-Zane Materials of Zanesville proposes one for the northwest side along Raccoon Creek at 2699 Johnstown Alexandria Road (Rt. 37), which is the Martin Trucking property. A Scioto concrete-mixing plant already operates on that site.

Halton said it is EPA practice to consider such plants individual, and not collectively.

Although the focus of last week’s hearing was the proposed air permit for the Scioto Materials site, questions were raised about water concerns and permits previously issued.

Amy Klei, chief of the EPA Division of Drinking and Ground Waters, said: “Discharges from these types of plants, we do not expect to see impacts from surface and ground waters.”

She explained the greatest concern comes from stormwater, but this should not be an issue, based on modeling that the EPA does. Klei said that additional protection for residential wells and drinking water is a 20-30 foot clay layer.

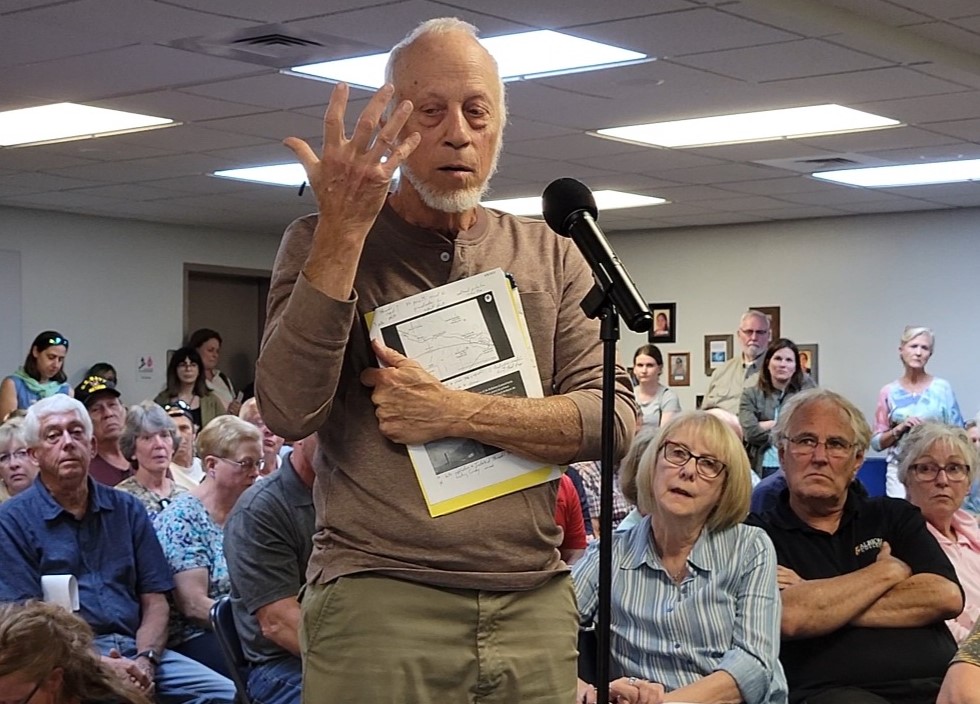

Tod Frolking, emeritus professor of geosciences at Denison University, disputed that statement, saying that there are direct connections from the surface down to the aquifer. That aquifer charges the water well field from which Alexandria and Granville get their drinking water.

Frolking said he has taken many core samples in the area, and the geology of the area is porous.

“There is no 20 feet of clay”in Raccoon Valley, Frolking said.

Later, Paul Ohl also disputed the EPA statement and agreed with Frolking. He said he had dug a pond on his property along Raccoon Valley Road between Alexandria and Granville. The first two feet were topsoil, below that was peat, below that was 3 to 5 feet of clay, then gravel.

“So that 20-30 feet of clay in that report is a fallacy,” Ohl said.

Granville Mayor Melissa Hartfield was the first to give a testimony against the air

permit for the asphalt plant.

“People are not opposed to an asphalt plant, but to the location, due to potential damaging impacts,” said Hartfield. “It’s Shelly Company’s responsibility to find [a suitable] location. Not mine, not [the EPA’s], and not anyone else in this room.”

Hartfield expressed her concern about Granville and Alexandria’s water supply.

“I want you to know that the Village of Granville intends to aggressively oppose this proposal, at every step, through every process, to protect our air and water as well as our quality of life,” said Hartfield

Stephanie Taylor, a registered nurse from Alexandria, asked that children’s health be considered. She argued that children metabolize toxins differently, and more quickly, than adults. Taylor pointed out that there are four school-bus stops on Main Street in Alexandria, and she expressed her concern about trucks hauling materials traveling past these children.

Several questions and concerns were raised about the truck traffic that would come with the proposed plants, and how diesel exhaust might affect the air. But according to Halton, truck exhaust and traffic do not fall under EPA’s jurisdiction, and there are no exhaust standards for the EPA to enforce.

Ken Apacki, a Granville resident, said he read the proposal for the Scioto Materials plant. He calculated how many trucks would go through Alexandria under this plan. He estimates 700-900 trucks a day in a 12-hour work day to supply the plant with raw materials and haul out the asphalt. If that one plant runs 24 hours a day, seven days a week, it would require 1,500-1,900 trucks a day running day and night.

Andrew Bottar-Dillen, a representative to Alexandria Village Council, testified at the last minute, with his young son Neil by his side. He didn’t want the evening to pass with no elected officials of Alexandria standing up to speak.

Bottar-Dillen lives on East Main Street, and he said the truck traffic on that road is already out of control.

“When these trucks are flying down the street my windows rattle. My son plays in his front yard and gets covered in dust. He comes in and he’s filthy. I have to give him a bath,” Bottar-Dillen said.

“This is a human impact. Let’s do a better job. Let’s find somewhere else” for these plants, he said.

Caroline Zollinger writes for TheReportingProject.org, the nonprofit news organization of the Denison University Journalism Program, which is sponsored in part by the Mellon Foundation.