To understand the nature of the landscape around central Licking County, and the flow of water through it, you have to talk about glaciers.

Before the glaciers, most of today’s creek and river valleys were deeper and steeper-sided, rocky canyons which had been carved through geologic time by watercourses which may not have even gone the same direction as today’s flow.

Some of those ancient rivers and lakes were identified and discerned by geologist William G. Tight. Born in 1865 and raised in Granville, his giant natural boulder grave marker (very on brand) is just to the left inside the gates of Maple Grove Cemetery.

Lost watercourses like the Teays River or Glacial Lake Tight — he described it, so he named it — were part of that world reshaped by the powerful flow of millions of gallons of melting glacial ice. The mysterious Blackhand Gorge was carved through a hundred feet of sandstone in that geologically recent era.

More importantly for our landscape, though, were the glacial outwash sediments, carried along by the melting ice water. Those older, steep-sided valleys were filled with a dense deposit of clays and fine gravel. It’s soil, not bedrock, but solid enough to attract the U.S. Air Force to just south of Newark in the early 1960s. Those deep glacial outwash deposits were ideal for drilling shafts to use in recalibrating inertial guidance equipment for aircraft and missiles — a shaft through solid stone would vibrate with passing traffic in ways that would interfere with the work being done.

Interestingly, these “second terraces” above the river bottoms but below the peaks and ridges of today’s Welsh Hills and Flint Ridge turned out to provide a wide, broad, level platform two thousand years ago for building alignments to monitor the horizon, calibrating the heavens, in a sense. The Newark Earthworks needed big open flat spaces with a clear view of the rise points of the sun and moon to the east and their setting to the west, and these high terraces were ideal then for Native American watchers of the skies, as their depths were ideally constituted for Air Force observers and technicians more recently.

What has also dramatically changed, long after the glaciers have retreated, is the behavior of rivers in their stream beds. Once the glaciers were entirely gone to the north, their last meltwaters began to carve more shallow, wide valleys through those sediments which filled the older, buried canyons below.

These were wide valleys because the slower drainages, with intermittent spring floods and other seasonal peaks speeding things up on occasion, cut differently along their way east to Blackhand Gorge and on to the Muskingum River beyond. The slower post-glacial streams would meander along their valley floors, snaking and twisting, seeking the lowest points and paths of least resistance, creating ox-bow bends.

When a powerful flood stage would lift all the waters, sometimes the main channel would change, isolating the occasional ox-bow lake or changing a secondary channel to primary. These cycles meant that in general our rivers in the last few thousand years tended to go slower, shallower, with some broad backwaters, the snaking path occasionally lashing from one side of a valley to the other, and a century or two later back again.

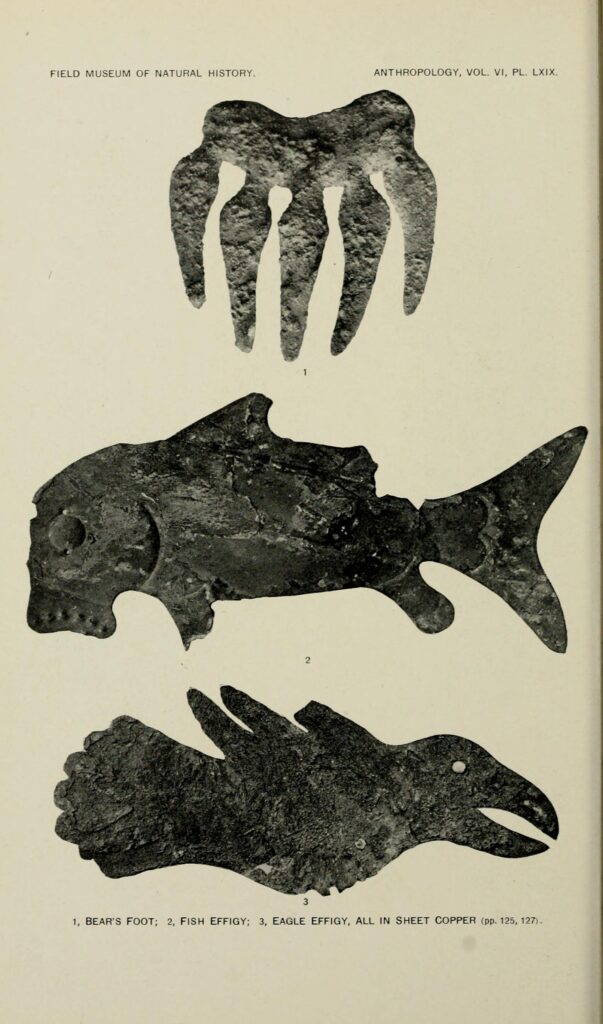

These waters, then, would be warmer in the summers, as well as slower moving, carrying some sediment with them as well. This meant a very different suite of fishes and mollusks, including sturgeon and high-protein paddlefish — part of the diet and life ways of Native American residents of the area — were once common here.

Euro-American settlement and their life ways meant a change in landscape management which drastically changed the ecosystem. Property owners and local governments preferred to channelize streams, keeping them in “their” banks as they’d found them in the early 1800s, which resulted in them moving faster, deeper, and colder. Sturgeon and paddlefish declined in this region along with other fish and mussels.

Today, Raccoon Creek is well-behaved in certain ways, locked into a channel alongside Ohio Rt. 16, no longer whipping back and forth from north to south as it flows over the years always (now) to the east, but faster now, and colder. And many creatures once common here we know better from ancient artifacts from the Hopewell Culture than from what we see on our riverbanks today.

Jeff Gill is a freelance writer, wandering storyteller, and occasional preacher in Granville, Ohio.